The Privatisation Myth and the Legacy of the NHS - 1

The history of the NHS was that of an institution that was the envy of the world. The future could be that of an institution that has been trashed by a corrupt political elite.

A month before the 75th anniversary of the NHS, I began working on this article. But my attention was diverted by events unfolding in the Middle East. Now, in a shift of topic from Palestine/Israel, I turn my attention again to the NHS. But I also focus on the wider issue of healthcare, especially in the light of dramatic recent events. I’ve split the article into 2 parts so that I can cover the full extent of the issue at hand.

On the 5th July 1948, a British institution was born. On the 5th July 2023, the National Health Service (NHS) turned 75. But will it survive another 75 years? This article will outline how the forces of neoliberalism is privatising the NHS by stealth, by creating faux solutions to accommodate the neoliberal cult that has become the dominant global system. I’ll also look at the ramifications of the assassination of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, representing a company that entirely encapsulates the neoliberal system. But lets go back to the start when the NHS was part of the post-war dream.

A Phoenix Will Rise

The NHS emerged from the ashes of World War 2 as post war Britain attempted to rebuild itself, its society and economy. The NHS was part of the new welfare state that was put into place by Clement Attlee’s newly elected Labour government that took power at the end of the war. But the NHS didn’t just appear out of nowhere. Its gestation had begun much earlier.

The NHS’s roots stem from the turn of the 20th century, when the Royal Commission on the Poor Law and the Unemployed was set up in 1905. Its remit was to investigate whether changes were required in the system at the time. The commission was divided and ended up producing two reports, a majority and minority report, both issued in 1909. Although their recommendations differed, they both ‘criticised the duplication and overlap of health services provided by voluntary and Poor Law institutions’. The majority report effectively reflected the views of the time, that the poor were responsible for their own predicaments. The minority report saw the need for reform, with a focus on prevention rather than cure, sowing the seeds for a future welfare state, although no major impact was drawn at the time from these reports.

Influential in the production of the minority report was Beatrice Webb (maiden name Martha Beatrice Potter), a social reformer and founder of the London School of Economics, who also played a crucial role in the formation of the Fabian Society. Her second husband Sidney Webb stood by her and helped with her research, through his extensive legal expertise.

William Beveridge, who would become the architect of the new post war welfare state, worked as a researcher for the Webbs’ on the Minority Report in 1909, as reported in a paper from the Fabian Society, From the Workhouse to Welfare. The Minority report has become closely associated with the Beveridge Plan of 1942. Both had a major influence on the debate on poverty and welfare in Britain. It should be noted though that there were positive elements in the majority report and that when these reports came out, the relative class divisions and inequalities that existed at the time were regarded as more pronounced than during the post war era. There were also some shortcomings in the Royal Commission’s deliberations, but that was perhaps more reflective of the period.

Although the Minority report was largely ignored by the Government, it had made an impact, particularly with Dr Benjamin Moore, a Liverpool physician, who developed some ideas. In 1911, he published the book ‘The dawn of the health age’ which first proposed the idea of a ‘National Health Service’. In the book, Moore formulates the concept of developing a National Medical Service, which would ultimately become a National Health Service, focusing on disease prevention as well as cure. He argued that funding for such a system could be ‘in part contributed by the workmen and in part by taxation.’ Essentially this would take the form of ‘a sickness insurance scheme.’

Following the publication of the book, Moore, along with Dr Milson Russen Rhodes, a GP, formed the State Medical Service Association. In 1912, Rhodes published the outline of a proposal for a National Medical Service, which laid down the basic principles for such a service. This followed on from the introduction of the Government’s National Health Insurance in 1911.

In 1929, further steps were taken through the 1929 Local Government Act, which abolished Poor Law Unions, as the country came to terms with social conditions post World War 1. This stemmed from the creation of the Ministry of Health in 1918, which set up a Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Services, leading to a report calling for greater provision of health services. These were geographical regions in England and Wales that were administrated under the poor law regulations. Similar regulations were enacted in Scotland. A year later the State Medical Service Association was superseded by the Socialist Medical Association.

The slow progress post World War 1 was due the subsequent economic slowdown during the 1920’s. The rise of the Labour movement during this period though would eventually set the stage for what was to emerge. The SMA became affiliated to the Labour party in 1934. In 1981 the SMA changed its name to Socialist Health Association, to reflect a shift towards the prevention of illness through the promotion of good health.

In 1937, fact met fiction through the publication of a novel by Scottish physician and novelist Archibald Joseph Cronin (known as A. J. Cronin). Cronin graduated from Glasgow University after serving in the Navy as a surgeon during the war. He then moved to Wales to take up a GP post. In 1924 he became Medical Inspector of Mines for Great Britain. He went on to take up a successful practice in London. But due to ill health he returned to Scotland and spent a period in the Highlands recuperating. It was then during the 1930’s that he took to writing and left medicine behind him. That eventually led to the publication of The Citadel in 1937. As this biographical account notes, in the book:

he drew on his medical background in the South Wales coalfields and in Harley Street to highlight the huge inequalities that existed in health provision in Britain at the time. "The Citadel" is often credited as the inspiration for the National Health Service, introduced in Britain in the years following the Second World War: and more widely the gritty social realism of Cronin's novels was believed by many to be an important factor in bringing about the landslide victory of the Labour Party in the 1945 UK General Election.

His influence was substantial. Many of his books became films or TV series, including The Citadel, which was released as a film in 1938.

His novella "Country Doctor," featured the character of Scottish doctor, Dr Finlay, which became a popular TV series produced by the BBC during the 1960s.

By 1941, as war raged, the Ministry of Health (now run by a wartime Conservative/Labour coalition) was formulating the initial framework for what would become the NHS. This resulted in the 1942 Beveridge Report (full title: Social Insurance and Allied Services). Sir William Beveridge had laid the foundation for the NHS, which would fall into place with Labour’s new Health Minister Aneurin Bevan, with the launch of the NHS on 5 July 1948. The rest as they say is history.

The current crisis

The current state of affairs can be ascribed to the rise of the global neoliberal system, not just in the NHS but in every aspect of economic and political life. I’ve covered neoliberalism before, particularly within the context of climate change.

This full section from the above article is reproduced in the following subsection.

The Roots of Neoliberalism

In a paper from the Annual Review of Anthropology, scholar Tejaswini Ganti from New York University, considers the role of anthropological research into neoliberalism. It outlines how neoliberalism has become a focal point within 21st century discourse as a political-economic concept. In the paper, Ganti argues that neoliberalism can mean different things depending on context. She identifies four key terms:

(a) a set of economic reform policies that some political scientists characterize as the “D-L-P formula,” which are concerned with the deregulation of the economy, the liberalization of trade and industry, and the privatization of state-owned enterprises; (b) a prescriptive development model that defines very different political roles for labor, capital, and the state compared with prior models, with tremendous economic, social, and political implications; (c) an ideology that values market exchange as “an ethic in itself, capable of acting as a guide to all human action and substituting for all previously held ethical beliefs”; and (d) a mode of governance that embraces the idea of the self-regulating free market, with its associated values of competition and self-interest, as the model for effective and efficient government.

Neoliberalism is referred to as an ‘ideological and philosophical movement’ or ‘thought collective’ that emerged during the interwar years. The driving force behind the ideology was the prevailing rise of communism, collectivism and state-centred planning. In short, socialism as a political force was seen as a threat to the free market and individual freedom.

The concept began to take shape before the outbreak of World War 2 with the publication of Walter Lippmann’s An Inquiry into the Principles of the Good Society in 1937, ‘which argued that a market economy was far superior to state intervention and that the absence of private property was akin to totalitarianism.’

After the war, the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS) was founded by a group of influential economists (named after the Swiss town where they met), led by by Austrian economist Friedrich August von Hayek, ‘to build a transnational network of intellectuals who could be trusted to promote the cause of neoliberalism.’ The key focus was private property:

Private property in terms of the means of production was seen as key to decentralizing power and preventing its concentration, which could otherwise jeopardize individual freedom. Freedom of choice across all domains of production and consumption—of the producer, worker, and consumer—was imperative for the efficient and satisfactory production of

goods and services. Freedom of choice also extended to individuals who should have the right to plan their own lives rather than be directed by a centralized planning authority.

Also in the team was Milton Friedman, who’s theories would have a major impact in the emergence of neoliberal thought… . But the seeds of the free market were sown in the 18th century by Adam Smith in his seminal work An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Smith referred to the market as an ‘invisible hand’, whereby someone pursuing their own interest ‘frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.’ This forms the basis of the modern concept, if you leave the free market to its own devices, everything will work out under its own volition.

Hayek was strongly influenced by Smiths work and that underpinned his position on the free market.

Corporate Health Care

One seminal work to emerge at the turn of the century was the film and book The Corporation by Joal Baken. The film can be viewed here. Bakin is a law professor at the University of British Columbia. His analysis in the Corporation is regarded as groundbreaking. Within the context of this article, Baken’s examination of the pharmaceutical industry (aka ‘Big Pharma’) is particularly instructive. He outlines how the corporate entity became a ‘legal person’ and how this legal person has become afflicted with every personality disorder you could possibly think of - the key diagnosis from his analysis being that the corporation is a psychopath with an absolute obsession with its bottom line. This particular aspect was settled in the court case Dodge v. Ford (1916) in which the Ford motor company was sued for withholding full share dividend payments. The key argument was that profits belonged to shareholders. The judge agreed and the ruling became integrated within corporate law. It became known as ‘the best interests of the Corporation’ principle and is applied globally. Bakan quotes corporate lawyer Robert Hinkley, who sums it up:

[T]he corporate design contained in hundreds of corporate laws throughout the world is nearly identical … the people who run corporations have a legal duty to shareholders, and that duty is to make money. Failing this duty can leave directors and officers open to being sued by shareholders. [The law] dictates the corporation to the pursuit of its own self-interest (and equates corporate self-interest with shareholder self-interest). No mention is made of responsibility to the public interest … Corporate law thus casts ethical and social concerns as irrelevant, or as stumbling blocks to the corporation’s fundamental mandate.

But what about ‘social responsibility’. We’ve been hearing a lot about that lately. Problem here though is that social responsibility is technically illegal under corporate law, unless it’s ‘in the service of corporate self-interest’, a point once raised by Friedman.

This then is the omnipresent entity that each and every one of us has become dependent upon from the cradle to the grave, a sentiment famously encapsulated in the Adbusters brand baby graphic.

In his analysis, Baken focuses on one of the biggest pharma companies in the world, Pfizer. He outlines some of the philanthropic activities the company engages in. But as with any other corporation, these are not conducted out of the goodness of their hearts. They must benefit the bottom line. This is reflected in the drug market. For example, Pfizer has a free drug initiative where it gives away free drugs perhaps to engage with medical professionals or to open up a potential market. But:

Pfizer can write off the free drugs as charitable donations and thus save itself money at tax time.

This is reflected in the wider market, where drugs for ailments like baldness or impotence are more profitable than developing drugs to treat killer diseases that afflict millions, particularly in developing countries. As such, ‘the 80% of the world’s population that lives in developing countries represent only 20 of the global market’, whereas in the west and countries such as Japan, the figures are reversed. I’ll cover Big Pharma in more detail later.

How does neoliberalism manifest itself within the industry? A paper published in the International Journal of Consumer Studies, Neoliberalism and health care (2001), by Sue McGregor (Professor, Department of Education, Coordinator Peace and Conflict Studies Program, Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, Canada) explores how neoliberalism is influencing health care in the main Anglosphere countries (UK, Canada, USA, Australia and New Zealand). The paper deftly explains the mechanisms of neoliberalism and the beliefs and ideas that drive it, whilst making reference to how it will ultimately impact health care.

Social policy is regarded as fundamental to a functioning democracy. The ‘three pillars of social policy’ comprise of education, social welfare/income security and health care. These are funded by taxes to maintain the general welfare of the population. All this is under threat and is being systematically undermined as the powerful and alluring cult of neoliberalism imposes its free market ideology. McGregor explains how this is happening by identifying ‘three principles of neoliberalism’.

As noted above, Adam Smith’s work formed the basis of what became known as liberalism. This became less prominent with the emergence of a more socialist orientation, underpinned by Keynesian economics during the 1930s. But change was afoot as the 1970s saw a pivot towards a renewed liberalism, hence the term ‘neo’-liberalism, ultimately driven by the ideas of Hayak and Freedman. These principles are: Individualism; Free market via privatisation and deregulation; and Decentralisation. The former is very much a me first free-for-all, with no concern for others or anything else. There must be no restrictions. This supposedly manifests itself as independence, focusing on ‘ownership of private property, competition and an emphasis on individual success measured through endless work and ostentatious consumption’. This of course will lead to a greater good. And:

In addition, neoliberalists eliminate the concept of the public good and the community and replace it with individual and familial responsibility. Advocates of neoliberalism believe in pressuring the poorest people in a society to find their own solutions to their lack of health care, education and social security. They are then blamed and called lazy if they fail.

Neoliberalists reject social policy as a form of discrimination as not everyone benefits. The belief is that everyone should be treated equally regardless, and no one should be given preferential treatment. The route to this is through privatisation and deregulation - zero government interference. Applied to health care, consumers spending in the market place will enhance health care provision as opposed to provision through taxes:

This position provides justification for a call for tax cuts to increase discretionary consumer spending on health care in the private markets – let consumers make their own choices.

In short ‘the free market regulates itself in order to create social justice (equal treatment for all)’. As we will see, this supposition is inherently irrational. It follows the flawed logic of trickle down economics, where profits and benefits ultimately descend to everyone else.

Decentralisation is another key plank in neoliberal policy. In health care, the argument is made that providing local services improves efficiency, enhances local delivery, streamlining, and avoiding duplication of services. This will cut costs. Problem is - it doesn’t work, according to the World Bank. As McGregor notes:

the World Bank concedes that there is little evidence that decentralization in health care actually works. For instance, devolving central government responsibilities for health care to local levels leads to more and smaller less accountable, less visible and less accessible health care centres. These services are often off-loaded onto smaller governments that do not have the ability or the money to offer the same level of health care service.

This then leads to problems whereby the public becomes convinced that the provision has become so bad that they have no choice but to turn to the private sector. This is summed up perfectly:

Neoliberalists assume that one cannot be a full citizen unless one has buying power in the marketplace. Those who cannot purchase health care are marginalised and are not part of social solidarity. Neoliberalists encourage individual choice at the expense of social responsibilities to others and nature. They arrange for the public health care system to become so inaccessible, undependable and inefficient that people feel they are making a good consumer choice by buying services in the marketplace.

This is precisely the process that is unfolding in the NHS. In her paper, McGregor cites some important recommendations to counter the neoliberal onslaught. She notes that:

Consumer affairs professionals who ignore the pervasiveness and insidiousness of the neoliberal mind set do so at the peril of individual and family welfare, especially their health.

It is vitally important that we understand the political logic behind health reform and to counter those who would advocate for such reforms. McGregor concludes:

It is time to reverse the trend to focus on the neoliberal metaphor of the consumer in the marketplace and replace it with the goal of democratic citizenship and a caring society. Cuts to, and dehumanization of, health care are not necessary and are avoidable. Equity, efficiency, quality, representation and accountability can be achieved without compromising the health of an entire nation and future generations. Health care needs to be restored to a level that achieves social justice and protects and enhances human life and dignity. Broadening our analysis of health care reform by understanding and challenging the neoliberal mind set is a first step towards humanizing health care policy.

Decentralisation is another issue that’s became part of the debate. There have been various studies comparing decentralisation with a more centralised system. A major report was produced by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies on behalf of the World Health Organization in 2007, along with a number of other agencies. It’s essentially a Europe wide study that compliments a series of reports that was produced by the Observatory. Although I haven’t analysed the report in detail, the gist appears to be that there is no one size fits all. Some degree of decentralisation could be effective but full scale decentralisation is questionable. Indeed the report points out that countries that embarked on a decentralisation policy have reversed some of the restructuring that took place within their systems.

This appears to be the message from other research. This paper from the National Library of Medicine (2019) gives a general overview of the situation. It also points out the lack of clear evidence and ambiguity involved in decentralisation. However it also points out that decentralisation isn’t necessarily the same thing as privatisation. Nevertheless the paper could inform health professionals.

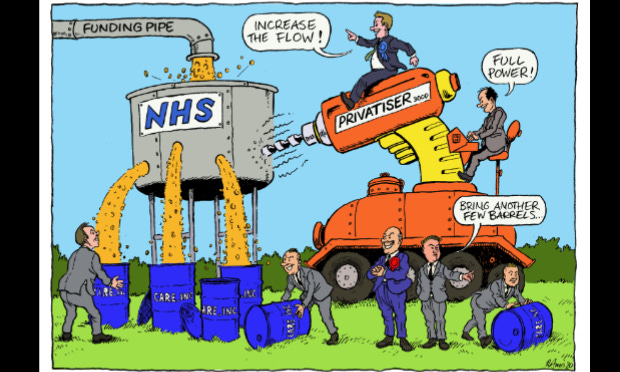

As for the privatisation argument, an article in the Lancet indicates that patient care could suffer under privatisation, however the article admits that its findings are not totally clear cut. Nevertheless there is a general consensus that the implementation of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act has served as a catalyst for the inevitable expansion of privatised services within the NHS, consolidating longstanding concerns of privatisation by stealth.

In 2021, the Real Media ran the headline, NHS privatisation by stealth - the selling of GP practices. Its focus was the take over of GP practices by a US health care company. I’ll get into the nitty-gritty of the issue of so-called US health care later. So, is the NHS being privatised by stealth?

The seeds of privatisation were sowed by Margaret Thatcher. It was all part of the neoliberal insurgence that was emerging on the back of Friedman and Heyak’s ideological visions. This article from the Margaret Thatcher Foundation offers some background:

One of the precursors of Thatcherism was a revival of interest in Britain and worldwide in the work of the Austrian economist and political philosopher, Friedrich Hayek, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 1974. Alongside Milton Friedman, who won his Nobel Prize in 1976, Hayek lent great prestige to the cause of economic liberalism, helping to create the sense of a rightward shift in the intellectual climate, valuable in all sorts of ways to MT [Margaret Thatcher] and others arguing the cause, such as Ronald Reagan.

This article from The Lowdown, the first of a series of articles covering the history of privatisation of the NHS, outlines how this was applied to the NHS. During the ‘80s the Thatcher Government engaged in an orgy of privatisation, where many public utilities were sold off to the private sector. The NHS wasn’t entirely excluded. It was a process of low profile outsourcing of services focused on cleaning, catering and laundry. It was initially called ‘compulsory competitive tendering’. But following Thatchers second term in 1983 it became the slightly more nuanced ‘Competitive Tendering in the Provision of Domestic, Catering and Laundry Services’. But at the end of the day it was all about saving money, nothing to do with providing genuine services. But it all didn’t go unnoticed. The unions were against privatisation and stepped up resistance, even the local health authorities we outraged. Eventually the whole process was exposed as a failure:

As Hillingdon Health Emergency summed up in 1984: “The important thing to realise is that privatisation is not being done to save money or to direct more finances towards patient care. The evidence indicates that it costs money rather than saves it and standards fall drastically. Privatisation is a political move to line contractors’ pockets and destroy the power of organised labour.”

This wasn’t lost even on some Tories and contractors wary of their reputation:

The relentless squeeze on standards also divided some of the Tories’ own supporters: in the autumn of 1984 Gardner Merchant, a catering subsidiary of Tory-donating Trust House Forte, pulled out of tendering for any of the NHS catering contracts to avoid reputational damage. “I have no desire to appear in the media accused of exploiting patients,” said MD Gary Hawkes, “Just imagine what it would do to us if we were running the catering where there was a food poisoning epidemic like there has just been in [Stanley Royds Hospital in] Wakefield.”

It wasn’t long before health authorities were throwing out contractors. But not to be swayed by inconvenient facts, the government overruled the authorities in favour of the contractors, regardless of how bad they were. Everything was done to render health authorities’ influence redundant. The end result was plunging standards within the NHS across the board. The scandal became amplified across the UK under Thatcher. Even worse, as this paper from the LSE outlines, the drop in standards resulted in the outbreak and spread of superbugs such as MRSA. The devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales though would reverse the rot in their countries at the turn of the century.

More was to come, as part 4 of the Lowdown series outlines. The whole debacle of privatisation would quietly shift from scandal to extortion. Neoliberalism’s ugly head was rising above the parapet. The Private Finance Initiative (PFI) saw the light of day in November 1992. Thatcher was gone. John Major was now in charge of the country. How the scheme worked was that:

PFI required projects above a certain minimum scale (in the NHS this was initially above £5m) to be opened up for bids from the private sector to finance the scheme, with repayments over a prolonged period of 25-30 years or more.

Implementing PFI meant breaking regulations that controlled public spending. As newly installed Chancellor Kenneth Clarke put it, “Privatising the process of capital investment in our key public services.”

The end result was that:

Rather than owning new hospital buildings, the NHS Hospital Trusts, (many still newly established, or just emerging after the controversial “internal market” reforms in 1990) would become lease-holders, required to make annual, index-linked payments for the use of the building and support services provided by contractors for the lifetime of the contract, which could be anything up to 60 years.

Hospitals built on this basis would no longer be public assets, but long-term public liabilities incurring increasing payments for a generation or more ahead. These capital schemes were not investments, but new forms of public sector debt.

In short, the whole process was a scam that was ‘parodied as “Profits For Industry”, “Profiting From Illness,” or simply “Pure Financial Idiocy”.’

Over time, there would be a steady flow of capital out of the NHS into private companies. The initial implementation of the PFI was fraught with problems, in the relentless stampede towards implementing the ideological gospel of privatisation. The irony was that it would be ‘New Labour’ who would establish the future legacy of the PFI.

After nearly 18 years of Tory rule, a new government was seen as a breath of fresh air. Tony Blair’s convincing rise to power in 1997 portrayed him as a saviour. It was one of several U-turns from the new government after having panned PFIs when the Tories introduced them. Blair would go on to follow through on many policies introduced by Thatcher. Indeed in 2002, Lady Thatcher - as she was then - was asked, what was her greatest achievement? Her answer, "Tony Blair and New Labour”.

Labour projected their PFI policy as a ‘third way’, ‘finding common ground between neoliberalism and social democracy.’ The policy was sold as being great value for money. Guardian financial columnist Larry Elliott described the PFI as a scam:

“Of all the scams pulled by the Conservatives in 18 years of power -and there were plenty -the Private Finance Initiative was perhaps the most blatant. … If ever a piece of ideological baggage cried out to be dumped on day one of a Labour government it was PFI.”

But neoliberalisms’ political and economic capture was complete. It was signed into to law. 15 hospital projects in 1997 were given the go-ahead. The first of those would be borne by the soon-to-be devolved nations, with Wales picking up 1 and Scotland 3.

Grace Blakeley writes a good piece for Novara Media. She outlines how a new public management (NPM) ideology that emerged from neoliberal thinking, which formed the basis of the free market mantra that would replace what was regarded as inefficient and bloated state mechanisms. She points out how PFIs was basically an accounting trick to sell PFIs. She notes that:

it has recently been revealed that some PFI contracts are costing the public 40% more than would have been the case had public money been used directly. According to the National Audit Office, over £200bn of taxpayers money is being funnelled into unproductive, financialised organisations like Carillion, only to enrich executives and shareholders, whilst leaving taxpayers to foot the bill.

In many cases PFIs racked up a catalogue of debts that left the government holding the can and having to step in. There has also been spectacular failures like the bankruptcy of Carillion. In short the only benefactors are those in the private sector siphoning off the spoils:

like most neoliberal governance innovations, is about carving up the state to the benefit of investors.

The Conversation picks up the story of ‘PFI at 30’, 30 years after the Tories hatched the scheme. It notes that more than 700 contracts were:

signed off in the UK until the government stopped doing them in 2018. They produced projects with assets worth approximately £60 billion, which are costing the taxpayer £170 billion – that’s a gap of £110 billion between what the assets are worth and what the taxpayer is paying for them.

PFIs initially covered a whole range of sectors, eventually penetrating into the NHS. It points out how risk was underestimated and how this led to the manipulation of accounts in some cases to cover up anomalies. It notes:

Sometimes failures to estimate risks helped to push contractors into bankruptcy. The classic example is Carillion in 2018, whose collapse was partly due to problems with PFI hospital contracts in Birmingham and Liverpool. Similarly with the London Underground modernisation in the early 2000s, poorly foreseen costs caused contractor collapses. The incomplete project reverted to the government, costing taxpayers billions of pounds.

But the risk doesn’t stop there. With some early contracts reaching the end of their lifetime, holding companies are not legally required to disclose assets. As such, there are many uncertainties surrounding these projects. Put simply, PFIs have been an unmitigated disaster.

Professor Allyson Pollock (Health Policy Research Unit, School of Public Policy, University College London), published the book NHS plc: the privatisation of our health care (2005). Pollock outlines how the NHS under New Labour became increasingly business oriented, with NHS management coming from a predominately business background, with little knowledge or experience in healthcare, and with public/private partnerships emerging with various sectors that included finance, construction and pharmaceutical companies. Another trend was the use of spads (special advisers) within government, who would represent a guiding light for the new direction of the NHS. At the same time the proverbial revolving door was installed as partnerships were forged with private enterprises. PFI contracts were beginning to take shape.

Thatcher’s Government began curbing union power, which would help improve efficiency and would open the door to outsourcing, focusing initially on general services such as cleaning and catering.

A report from Sir Roy Griffiths in 1983, paved the way for a new management culture at the NHS. Griffiths was the Deputy Chairman and Managing Director of J Sainsbury plc. He was asked to review initiatives to improve the efficiency of the NHS in England and to advise on management action needed to secure the best value for money and the best possible service to patients. A corporate style management structure followed and the outsourcing of non clinical services accelerated. The result was a decline in service provision. The book notes the impact of this, particularity on catering services:

the poor quality of hospital meals became notorious. Incredible as it might seem, 10% of seriously ill patients were found to have suffered malnutrition while they were in hospital.

In short, professionalism was being sacrificed on the alter of neoliberal business culture. It wasn’t long before other services such as dental and eye care migrated towards the private sector, with patients having to pay for those services. This also extended towards long term care, with the eventual proliferation of private care homes. The net result of these changes was:

In effect, for the most vulnerable people in society the NHS principle of equal care regardless of ability to pay had been abandoned.

With the system on the verge of collapse and suffering from a lack of proper funding, in 1987 there was a major public backlash. In response, Thatcher decided to modify the system through the creation of NHS trusts. But the underlying business ethos would not change. Indeed the whole idea behind the creation of the trusts was to engender a business culture. This was how the wholesale decimation of the NHS was set in motion:

the fragmentation of the hospital service into hundreds of separate trusts with purely financial obligations, and the ‘purchaser-provider’ split, set the NHS on a radically new path. These measures began the destruction of the NHS’s capacity to plan and distribute resources on the basis of the health needs of the population, and opened the way for the later moves towards the privatisation of clinical services.

Doctors lost their authority and were now subservient to management, with gagging clauses thrown in for good measure to prevent criticism from leaking out. This explains why there has been a culture of silence within the NHS up until this day. All the changes meant that funding was misappropriated. A reasonably well functioning system had been disrupted causing widespread chaos. What works for business is not the same as what works in the public sector. This was when the PFI was introduced via outside consultants. This would incur vast transaction costs and were complex to implement. It was when Blair came to power in 1997 that PFIs would really proliferate, despite the costs. Although perhaps not as extreme as Thatcher, all labour did was tinker around the edges. New hospitals were approved that would be funded by the PFI.

As is often the case in politics, evidence is ignored under the dogma of policy and ideology, Labour ignored the shortcomings of the PFI, as the book notes:

In spite of damaging expert criticism of the PFI in terms of its cost, efficiency and effects on services, and in spite of widespread pubic hostility as its failures in one field after another became apparent, Labour continued to pursue it with extraordinary determination.

The Government’s proposals were outlined in a white paper, whereby many hospitals would be subjected to the PFI process. Eventually it got to the stage where the governments whole approach to PFIs became farcical. It became apparent the real motive was the same noeliberal consensus that had drove the Tories. The PFI could open up lucrative business avenues, not just domestically, but globally also. There was therefore a foreign policy angle to the proposals. The PFI was effectively a scam. It sported a list of myriad failures:

More expensive than public funding

The payback was 30 -60 years

Switches the focus from health needs to business objectives

The cost comes from operating revenues

It wasn’t long before the ineffectiveness of PFI funded hospitals became apparent, with increased waiting times, rapid staff turnover, eventually yielding a shortage of staff. Ultimately this led to UK healthcare falling behind other countries. The government mantra was efficiency savings. These were never realised. Indeed the opposite was true. New hospitals were built smaller to cut costs. As a result they couldn’t accommodate demand.

As for the foreign policy angle, this was related to secret discussions within the World Trade Organisation (WTO) on the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) that aimed to open up public services to the private sector on a global basis. Such discussions would benefit US companies such as United HealthCare, looking to breakout from a saturated US market. The signing up of the UK government to the GATS provision would open the door to what we are now seeing in the NHS.

Bretton Woods and the NHS

Indeed the Bretton Woods institutions are the functioning organs of neoliberalism. Set up to provide finance and support after World War 2, these institutions became the World Bank, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the WTO. The WTO came into being in 1995, superseding the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), set up in 1947. I go into a lot of detail on BW here, providing some important context:

GATS is similar to GATT, as explained in this report from Sarah Sexton, Trading Health Care Away?: GATS, Public Services And Privatisation (2001). It governs international trade in services, whereas GATT governed international trade in goods. However GATS was more complex, as what defines a service is less tangible than a good. The range of services can be varied and country dependent. Here’s an attempt to define GATS:

David Hartridge, WTO’s former director of services, described GATS as “the first multilateral agreement to provide legally enforceable rights to trade in all services” and “the world’s first multilateral agreement on investment, since it covers . . . every possible means of supplying a service, including the right to set up a commercial presence in the export market.” According to the EU, GATS “aims to end arbitrary regulatory intervention, and assure predictability of laws, to generate growth in trade and investment”.

But there’s a flip side to this. Many saw GATS as the Multilateral Agreement on Investment rising from the grave. The MAI was binned after widespread protests at a WTO conference in Seattle in 1999 (see Paris article above). As the report notes:

Researcher Scott Sinclair says that GATS “is designed to facilitate international business by constraining democratic governance”. Indeed, the WTO expressly states that the Agreement will help its members overcome “domestic resistance to change” and that it will facilitate “more ambitious reforms . . . than would be attainable on a national basis alone”.

An article in The Lancet, How the World Trade Organisation is shaping domestic policies in health care (1999), elaborates what was at stake. It outlines the threat to democratic accountability and the fact that the WTO is dominated by corporate interests:

WTO trade agreements have been described as a bill of rights for corporate business.

The focus of the Seattle conference was GATS. The main thrust was that services are more lucrative than manufacturing, representing a substantial proportion of the economy. Not surprisingly the US was pushing for the opening up of health provision internationally. The article points out how different sectors related to health care, work to exploit the system, such as pharmaceuticals, care and health maintenance. The World Bank also came onboard to provide backing for the proposals. However persuading countries to open up their public health sectors to privatisation has been difficult. But as the article notes:

GATS permits member countries to force the removal of barriers to foreign participation in the service industries of other member countries. The WTO now has three main objectives: to extend coverage of GATS, to toughen procedures for dispute settlements so that member states can be more easily be brought into line, and to change government procurement rules to create market access.

This is where dispute settlement comes in. There are many documented cases of corporations suing governments over trade disputes. As the article notes:

Dispute settlement is an important means of US influence and a vital weapon in its trade expansion.

And the US uses its weapon aggressively and extensively. I documented dispute settlements and trade agreements extensively here:

The World Bank has encapsulated the cognitive distortions within the neoliberal mindset. As the Lancet article notes:

The World Bank has famously described public services as a barrier to the abolition of world poverty. It maintains that, “if market monopolies in public services cannot be avoided then regulated private ownership is preferable to public ownership”.

It goes without saying that the UK has been keen to endorse the doctrine of privatisation, particularly under New Labour. The net result is a fracturing of local accountability and responsibility for care, what the article describes as ‘democracy versus consumerism’. It sums up the predicament:

Income and health inequalities continue to widen in the UK. The restrictions on national sovereignty imposed by the WTO through GATS will make it increasingly difficult to reverse these trends.

The Lancet article hit the nail on the head at the time, considering that GATS was still regarded as incomplete and a work in progress. But there was a general view that it would continue to develop liberalisation policies. This is very pertinent to the UK post Brexit, as the UK is now under the auspices of the WTO. A report from the The NHS Confederation, The NHS and future free trade agreements (2019), offers an overview of what might happen to the NHS under GATS. However the gist of the report seems to revolve around familiar government assurances, whilst attempting to strike a balance between the pros and cons of provision under GATS. The general conclusion appears to be that the government of the day will decide what trajectory the NHS moves in under GATS. Meanwhile the World Bank is extolling the virtues of universal health care. The problem with the World Bank though is that it tends not to notice the elephant in the room.

US Healthcare

The working example of privatised healthcare is the US system. A report from the Commonwealth Fund, Mirror, Mirror 2024: A Portrait of the Failing U.S. Health System, offers an insight into how the US system compares with other high income countries. The conclusion? Not particularly well. That’s despite the fact that US expenditure on health is generally higher than other countries. The countries involved were: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The UK still remains one of the top performers, despite recent changes.

Affordability and availability of health services is a particular bugbear for Americans. As the report notes:

With a fragmented insurance system, a near majority of Americans receive their health coverage through their employer. While the ACA’s Medicaid expansions and subsidized private coverage have helped fill the gap, 26 million Americans are still uninsured, leaving them fully exposed to the cost drivers in the system. Cost has also fuelled growth of private plan deductibles, leaving about a quarter of the working-age population underinsured. In other words, extensive cost-sharing requirements render many patients unable to visit a doctor when medical issues arise, causing them to skip medical tests, treatments, or follow-up visits, and avoid filling prescriptions or skip doses of their medications.

This creates a nightmare for people making insurance claims, with a myriad of plans to choose from and the likelihood of claims falling through, causing massive health bills for patients, many of whom can’t afford them. The net result is a population that has a lower life expectancy than the other countries. The statistics speak for themselves:

the U.S. has the highest rates of preventable and treatable deaths for all ages as well as excess deaths related to the pandemic for people under age 75. The ongoing substance use crisis and the prevalence of gun violence in the U.S. contribute significantly to its poor outcomes, with more than 100,000 overdose deaths and 43,000 gun-related deaths in 2023 — numbers that are much higher than in other high-income countries.

This article from the Commonwealth Fund looks more closely at the insurance issues plaguing Americans. It reports around a third of working people get into debt, much of this due to billing errors and denials of coverage by insurance companies. The findings of a survey include:

More than two of five respondents reported either they or a family member received a bill or were charged a copayment in the past 12 months for a health service they thought was free or covered by their insurance.

Of the respondents who thought they had received a bill in error, fewer than half attempted to challenge the bill. …This is despite the ACA’s [affordable care act] requirement for insurers to have systems in place for consumers to appeal and challenge their bills.

Despite these protections, less than half of those denied coverage for a recommended procedure challenged the denial.

Of those who did not challenge their bills, over half said it was because they were not sure they had the right to do so.

Nearly two of five adults who challenged a bill said the amount was ultimately reduced or eliminated. People with Medicare or Medicaid reported higher rates of bill reduction or elimination.

Seventeen percent of respondents or one of their family members were denied coverage for care recommended by a doctor, and these rates were similar across insurance types.

Denial of coverage was responsible for many health problems getting worse, sometimes resulting in death. As the report sums up:

The complexity of the health insurance system in the United States has left many people struggling to understand what services are and aren’t covered, and their financial liabilities when they get care. On top of this complexity, insurers are motivated to avoid paying for care. Many insurers appear to be utilizing increasingly aggressive tactics to do so, deploying technology and applying pressure to company physicians to scrutinize services recommended by patients’ physicians and often to deny coverage, leaving patients with unexpected bills or delays in care.

The report makes reference to a series of investigations from ProPublica that exposes the abuses of the Insurance Industry. In short, there is no guarantee that an insurance claim will cover the extent of a medical claim. Challenging a rejection can be complex, which may involve litigation against an insurer. This can also be frustrating for medical professionals trying to treat patients. Its worth examining some of the cases covered by ProPublica here.

The first involves a student, who was enrolled on a UnitedHealthcare health insurance plan for students at Penn State University:

Christopher McNaughton suffered from a crippling case of ulcerative colitis — an ailment that caused him to develop severe arthritis, debilitating diarrhea, numbing fatigue and life-threatening blood clots. His medical bills were running nearly $2 million a year.

This was causing a financial headache for United. As a result United pulled out the stops to curtail McNaughton’s treatment. He had been put on a specialist treatment that had managed to control his condition. However, what made this case stand out was the determination of his family to fight the case with a lawsuit against United. The case revealed that United had obfuscated their intent, as they attempted to convey the impression that McNaughton’s health care was paramount, whilst pushing to reduce the doses of the expensive medication he was using. Evidence pointed out that that could cause his condition to regress, which would be catastrophic for him. This could also result in severe financial hardship for the family having to pay extortionate medical bills. What the case also exposed was the vagueness of some elements within insurance policies that can be difficult to understand and interpret. The bottom line was that McNaughton’s treatment was costing United around $1.7 million in the prior plan year. In contrast:

UnitedHealth Group filed an annual statement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission disclosing its pay for top executives in the prior year. Then-CEO David Wichmann was paid $17.9 million in salary and other compensation in 2020. Wichmann retired early the following year, and his total compensation that year exceeded $140 million, according to calculations in a compensation database maintained by the Star Tribune in Minneapolis. The newspaper said the amount was the most paid to an executive in the state since it started tracking pay more than two decades ago. About $110 million of that total came from Wichmann exercising stock options accumulated during his stewardship.

The company registered a profit of of $20.1 billion. McNaughton’s mother put that into perspective:

she told university administrators that United could pay for a year of her son’s treatment using just minutes’ worth of profit.

Eventually following the suit, United continued with McNaughton’s treatment regimen. Apparently the situation is subject to ongoing review.

The second case brings another healthcare corporation under the spotlight - Cigna. The company was exposed by Nick van Terheyden, a physician and a specialist who had worked in emergency care in the UK. He developed a vitamin D deficiency that can lead to osteoporosis. He received a denial letter from Cigna after submitting a claim for his treatment. He was immediately suspicious. An investigation found that:

The company has built a system that allows its doctors to instantly reject a claim on medical grounds without opening the patient file, leaving people with unexpected bills, according to corporate documents and interviews with former Cigna officials. Over a period of two months last year, Cigna doctors denied over 300,000 requests for payments using this method, spending an average of 1.2 seconds on each case, the documents show.

Most states have regulations that insist in a proper review of a patients medical records, but Cigna bypasses those processes. Cigna denied the findings of the investigations.

Cigna uses a review system called PXDX, which was developed by former paediatrician, Dr. Alan Muney. He had managed health insurance for companies linked to Blackstone, the private equity firm. He was also an executive at UnitedHealthcare, where he developed a similar system. In short:

Within the world of private insurance, Muney is certain that the PXDX formula has boosted the corporate bottom line. “It has undoubtedly saved billions of dollars,” he said.

As for van Terheyden, he had continuously received rejections from Cigna, stating that his blood test, which revealed his condition, was unnecessary. But he continued to appeal. Eventually an independent doctor reviewed his medical record and determined the test was justified.

Another revelation found by ProPublica was the fact that doctors who had been exposed for malpractice or other unethical practises were being hired by insurance companies. In a few cases the doctors had been subjected to lawsuits with payouts running into several $million. They’re also well paid:

The median pay for medical directors at insurers like UnitedHealthcare, Cigna and Elevance is around $300,000 a year, with the high end of the salary range over $400,000, according to the job site Glassdoor.

But there’s more to the US health insurance racket. Another less familiar entity exists in the background. These are outsourcing companies that are used by the insurance companies that conduct what is known as prior authorisations. These are the doctors’ requests for payments for treatments. The biggest player here is EviCore, which uses algorithms driven by AI to issue decisions on medical reviews. In short, it’s a cost effective way to issue denials on behalf of insurance companies. Although the algorithm itself doesn’t issue denials per se - the final decision rests with the doctors - this is how it would work:

The algorithm reviews a request and gives it a score. For example, it may judge one request to have a 75% chance of approval, while another to have a 95% chance. If EviCore wants more denials, it can send on for review anything that scores lower than a 95%. If it wants fewer, it can set the threshold for reviews at scores lower than 75%.

“We could control that,” said one former EviCore executive involved in technology issues. “That’s the game we would play.”

Some of the physicians working at these companies have become disillusioned by their practises. One stated:

“Most of the physicians who work at these places just don’t care,” she said. “Any empathy they had is gone.”

Relying on algorithms to determine healthcare so succinctly sums up the entire neoliberal ecosystem.

In the next part of this analysis, I’ll be looking at the pharmaceutical industry and examining what can be done to prevent the privatisation of the NHS, through a major campaign that has been gaining traction over the past few years. Just click on the ‘next’ button below.

This is invaluable. Thank you. Brief anecdote: in 1988 I was living and studying in Lancashire as an American exchange student. I came down with bronchitis and was keeping half the students in my college awake with my coughing. Finally one asked why I didn't simply go to the doctor. "Well, I don't have insurance and I can't afford it." My fellow, British, students looked at me like I had suddenly sprouted three heads. "You don't PAY to go to the doctor!" "Well, YOU don't. It's your country. But I'm a foreigner." "So?!" I saw a doctor, he diagnosed me and prescribed meds, and my mates and I were finally able to sleep well for the first time in weeks. My health affected the public well-being, and the state recognized that. What a concept!!

An exceptional article!