Geoengineering - Another False Solution to the Climate Crisis

We've failed miserably to tackle the climate crisis. Now it appears the only solution is Hi Tech and the Free Market. What could possibly go wrong?

In April 2025, the Guardian reported on a UK Government plan to introduce a solar geoengineering (SG) research project, via the government agency the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA). On the ARIA website it states:

Backed by £56.8m, this programme will explore whether approaches designed to delay, or avert, climate tipping points could be feasible, scalable, and safe.

It admits that:

there is a dearth of robust data on these approaches, and we have a limited understanding of whether such interventions are scientifically sound, how they might be steered, or the full extent of their potential impacts.

ARIA has published a program thesis, which I’ll unpack below. So, what is SG and why has it been largely discredited. Friends of the Earth gives a brief outline. It notes there are two general categories: carbon dioxide removal, through natural methods such as planting trees and restoring depleted land, or Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), which I’ve covered previously.

Secondly - what we’re interested in - solar radiation management (SRM), involving putting sulphate aerosols high into the atmosphere, to replicate the cooling affect of volcanic eruptions, and marine cloud brightening, with ships seeding clouds with tiny droplets of seawater to enhance their reflective capacity.

The key concern is that these processes are seen as a cheap quick fix to tackle the climate crisis, which could undermine what needs to be done. To understand how we got here, I’m going look initially at the concept of Environmental Ethics.

Environmental Ethics

This article from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, fundamentally considers the moral and ethical ramifications of the consequences of human actions on the environment. An important element here is the distinction between instrumental values and intrinsic values. Put simply:

The former is the value of things as means to further some other ends, whereas the latter is the value of things as ends in themselves regardless of whether they are also useful as means to other ends.

A plant may have an instrumental value for people if it has medicinal properties, but it may also have intrinsic value if it’s good as an end in itself. However intrinsic values tend be be predominately anthropocentric, which assigns:

a significantly greater amount of intrinsic value to human beings than to any non-human things such that the protection or promotion of human interests or well-being at the expense of non-human things turns out to be nearly always justified.

This can lead to a teleological perspective, whereby nature is there to be controlled and exploited for our benefit. The idea emerged in the 1970s as a challenge to anthropocentrism, questioning the assumed moral superiority of human beings over nature, and the consideration of assigning intrinsic value to the natural environment. But the triggers came a decade earlier. One particular landmark book that raised awareness of human impacts on the environment was Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1963), which I covered here.

I quoted this paragraph from the book, which sums up the impacts of agrochemicals:

As crude a weapon as the cave man’s club, the chemical barrage has been hurled against the fabric of life — a fabric on the one hand delicate and destructible, on the other miraculously tough and resilient, and capable of striking back in unexpected ways. These extraordinary capacities of life have been ignored by the practitioners of chemical control who have brought to their task no “high-minded orientation,” no humility before the vast forces with which they tamper.

The Encyclopedia notes:

While Carson correctly fears that over-use of pesticides may lead to increases in some resistant insect species, the intensification of agriculture, land-clearing and massive use of neonicotonoid pesticides has subsequently contributed to a situation in which, according to some reviews, nearly half of insect species are threatened with extinction, Declines in insect populations not only threaten pollination of plant species, but may also be responsible for huge declines in some bird populations and appear to go hand in hand with cascading extinctions across ecosystems worldwide.

How did we get here? The Encyclopedia refers to the work of Lynn White, who outlines the significance of the Bible on religious thinking:

Central to the rationale for his thesis were the works of the Church Fathers and The Bible itself, supporting the anthropocentric perspective that humans are the only things on Earth that matter in themselves. Consequently, they may utilize and consume everything else to their advantage without any injustice. For example, Genesis 1: 27–8 states: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over fish of the sea, and over fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

The emergence of Christian theology based on these constructs created the base for human domination over nature, which also became imbued within scientific thinking.

Another angle which influenced emerging ecological awareness was population growth. The book The Population Bomb (1968) by Paul R. Ehrlich, contended that a population explosion would threaten the viability of planetary life-support systems. At the same time an iconic picture taken of the Earth in 1968 by Apollo 8, orbiting the Moon, caused a sensation.

Another seminal work that came out in 1972, was Limits to Growth, produced by MIT, which I look at here.

I quote from the introduction, summing up the pressing issues that we face:

...the arms race, environmental deterioration, the population explosion, and economic stagnation are often cited as the central, long-term problems of modern man. Many people believe that the future course of human society, perhaps even the survival of human society, depends on the speed and effectiveness with which the world responds to these issues. And yet only a small fraction of the world's population is actively concerned with understanding these problems or seeking their solutions.

This led to further research and development into environmental impacts. It was during the 70s that the many of the ideas that we are familiar with today began to take shape, influencing environmental ethics and politics.

An important development that emerged during this time was the concept of Deep Ecology, influenced by the ideas of Norwegian philosopher and climber Arne Næss. He gained Inspiration from Sherpa culture in the Himalayas, who regarded certain mountains as sacred, as well as general reverence for nature. In making a comparison with ‘shallow’ ecology:

The “shallow ecology movement”, as Næss (1973) calls it, is the “fight against pollution and resource depletion”, the central objective of which is “the health and affluence of people in the developed countries.” The “deep ecology movement”, in contrast, endorses “biospheric egalitarianism”, the view that all living things are alike in having value in their own right, independent of their usefulness to others. The deep ecologist respects this intrinsic value, taking care, for example, when walking on the mountainside not to cause unnecessary damage to the plants.

Naess also notes that through deep ecology, humans can be less selfish and more self aware. Rather than an individual focused through the ego, one can engage with and be aware that we have an intrinsic relationship with nature, which can contribute significantly to our life quality.

The issue of deep ecology has engendered debate, with some suggesting that it’s more relevant to the global north, a sort of elitist environmentalism. Others see it as utopian. However it does resonate with many environmentalists and campaign groups as a buffer to the excesses of neoliberalism, and that human perceptions are irrelevant, nature exists and so do humans and we are as intrinsically a part of nature just like a rock or a beetle. This is exemplified in indigenous cultures, who are integrated within the ecosystems they live within, not separate entities like western culture. To widen the debate, perhaps intrinsic value itself is irrelevant. If a meteorite was to hit the Earth, the impact would be devastating and we would have no control over the event. However ecosystem services are also relevant. In that respect the influence of the Gaia hypothesis has been influential. It postulates that:

all organisms and their inorganic surroundings on Earth are closely integrated to form a single and self-regulating complex system, maintaining the conditions for life on the planet.

The Encyclopedia mentions Gaia within the context of a global terrestrial feedback system, under threat from human disruption. It notes:

In place of a vision of a grand cosmic self, champions of Gaia theory argue for recognizing the value of Life itself, where the capital "L" draws attention to the great feedback system—a single entity comprising all the living things descended from the last universal common ancestor.

In contrast to deep ecology is the concept of social ecology. The key difference here is that deep ecology focuses on intrinsic value, while social ecology focuses on a balanced relationship between society and the environment. This then shifts into the realms of bioregionalism, a concept outlined here by Earth.Org.

The article notes the impact of neoliberalism and the apparent benefits of being able to access goods and services from anywhere in world in your local supermarket. But this masks an invisible anomaly. Our life styles have marginalised communities in the global south:

This system also has clear drawbacks and very tangible failures, mostly tied to overexploitation in resource-rich developing countries and an overreliance on international supply chains to maintain even the most basic living standards. The more interconnected and complex our world has become, the more fragile and vulnerable to unforeseeable disruption our systems and institutions are.

The root of the problem is overconsumption and exploitation of natural capital, causing inequality in the global south. This generates an ecological imbalance, whereby almost 25% of global emissions come from the production and distribution of traded goods and services. Bioregionalism is seen as a counterbalance to the neoliberal system:

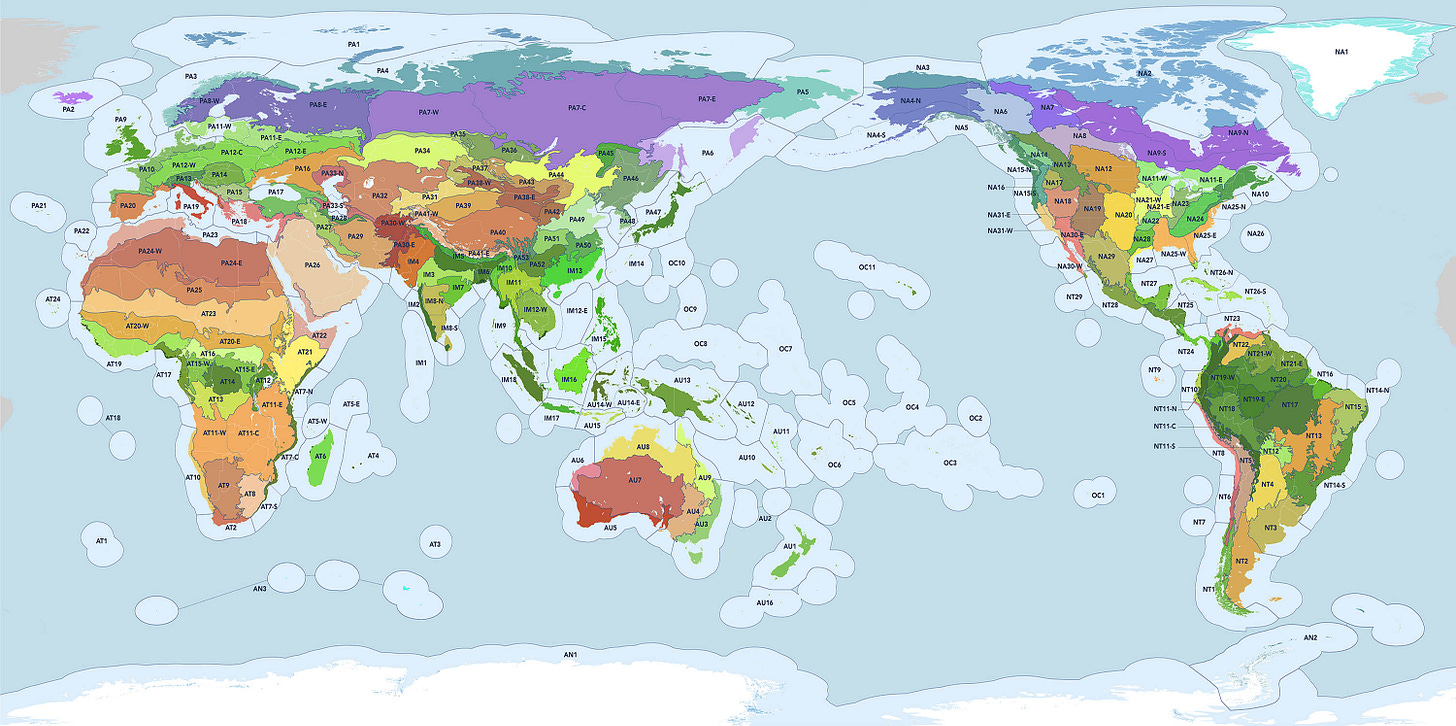

Ecologically speaking, a bioregion is a specific geographic area that is distinct from others by the characteristics of its natural environment. A bioregion is larger than an ecosystem, and is in fact usually host to several. A bioregion is large enough to encompass all the biological activity and ecological processes necessary for life to sustain itself, and for local habitats and ecosystems to preserve their biological integrity. Bioregions are often used by environmental organisations and government departments to plan and map biodiversity conservation efforts. They are certainly influenced by administrative and political boundaries, but are neither defined nor constrained by them.

Bioregions tend to share cultural similarities. This aims to cultivate community and ecological awareness, and localising the production of goods, becoming economically self-sufficient. This, theoretically, would decentralise the current system thus improving sustainability, increasing local community participation.

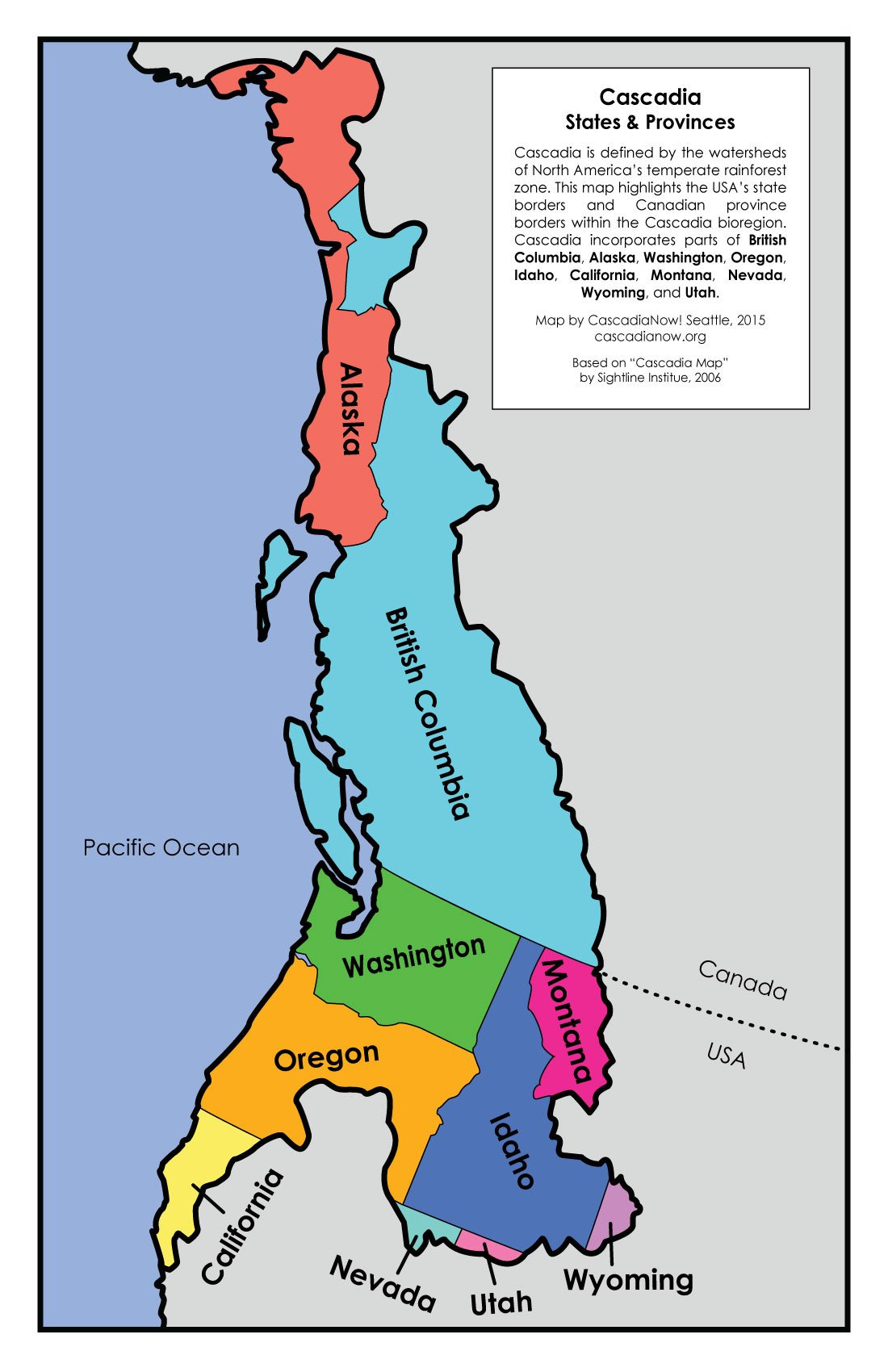

Whether bioregionalism could work on a large scale e.g. within megacities, is a matter for conjecture. It would be difficult to localise production for a large local population. However there have been smaller scale projects. Transition towns operated on a local basis utilising similar ideas to bioregionalism. The first transition town was Totnes in the UK, established in 2006. Since then the idea has spread across the globe. There’s an effort to establish a larger entity by the Cascadian secessionist movement, a bioregion extending across Southwestern Canada and the Northwestern US.

The article sums up:

There are clearly many obstacles to overcome before anything even resembling a bioregional economy could be implemented. What bioregionalism offers is an alternative to our increasingly globalised markets and models of governance. Legislation that is more participatory and personalised can reflect the critical public interests of environmental integrity and sustainable extraction of resources. Localised economies may be better suited to achieving these outcomes, but in lieu of a radical reorganisation of our political boundaries, strengthening institutions, public trust in government and creating a more direct form of democracy can support self-sufficiency and sustainability goals.

Expanding the analysis, the paper, A learning journey into contemporary bioregionalism, is published by People & Nature. Bioregionalism is defined as an environmental philosophy, which:

promotes human communities being organised within naturally defined units of bioregions, encouraging a shift towards ways of living that are enabled and constrained by the landscapes and ecologies that we inhabit.

The paper notes Peter Berg’s initial influence on developing the concept:

Bioregions are geographic areas having common characteristics of soil, watersheds, climate, and native plants and animals that exist within the whole planetary biosphere as unique and intrinsic contributive parts.

Bioregions can be seen as an integration of smaller ecological systems. They can also account for cultural influences, although this can be contentious. In an environment where indigenous people inhabit an area where western culture also prevails, what cultural aspects and politics are taken into account?

The paper pulls together social–ecological systems (SES) research and human–nature connection (HNC) studies. These are respectively, systems of people and nature, and, the interactions and experience of humans within nature.

The researchers found key drivers behind the endorsement of bioregionalism. There’s the focus on non-humans in relation to taking sustainable action, which connects to the idea of deep ecology. Viewing bioregional units in a global context provides strategic clarity relative to global patterns of consumption, trade and governance, and how to change the construct. Also the bioregion localises awareness, providing a tangible interface for people to engage meaningfully, initiating change in what would otherwise be more abstract and complex notions. This table from the paper encapsulates the key motivators behind the concept.

Bioregionalism actually isn’t new, particularly within the context of non-Western ideas and settler colonial politics. Specifically bioregionalism was a natural constant in past during the early days of human evolution. To note:

it's really important to just say, we've been bioregional all along, like, it's not a new idea. It's a return to the pattern that actually worked to enable our species' evolution.

In short, bioregionalism is simply a return to our formative roots. However there were contesting views about how the concept of bioregionalism should be fully realised, e.g. within a megacity. The concept would probably be largely alien to the average city dweller. And importantly:

The global economic system actually stops healthy bioregional economies from evolving.

These are important challenges that seek to inform the discourse, engaging people to find some form of meaning and increased awareness. There’s no specific formula. It’s a process of evolution. This can be shaped through the socio-ecological contexts of different places around the world and the local perceptions of individuals:

what is accessible, relevant and useful differs based on our experiences and contexts and how we process those exposures.

Bioregionalism is in a state of flux. Nevertheless it does present a conceptual and epistemological framework for pursuing sustainably. To explore this issue further, we need to also look at neoliberalism. The paper, Understanding the relationship between ethics, neoliberalism and power as a step towards improving the health of people and our planet (2018), published by, The Anthropocene Review, unpacks the issue. It highlights how scientific progress during the 20th century ‘generated a dualist conceptualisation of nature’ leading to the perception of human superiority over nature, there to be exploited for economic benefit. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, ‘neoliberalism has triumphed as the prevailing and dominant paradigm of global capitalism’. It notes that:

These patterns have been driven, in part, by an unsustainable energy-intensive, wasteful, consumerist, individualistic and ecologically myopic lifestyle which we have called a neoliberal capitalist ‘market civilisation’.

As a result, we have engaged in a ‘Great Acceleration’ over the past 40 years, which has impacted our symbiotic relationship with the environment, which we depend upon for our survival. This:

must lead to consideration of how we have reached a point at which all future life on our planet will be increasingly threatened by climate change, environmental degradation, ongoing emergence/rapid spread of potentially fatal infections, relentless increase in antibiotic resistance and other critical tipping points beyond which irreversible entropy will escalate.

The characteristics of neoliberalism, revolving around the competitive individual, amongst other things, results in ‘a form of egoism that operates within increasingly coercive and destructive frameworks of power’. And as we continue on a trajectory of unsustainability and increasing inequality:

It seems to us that we cannot hope for a more peaceful and secure world when conditions of life remain so inadequate for so many, and we continue to consume exponentially without concern for the future.

The paper links five key impacts of neoliberalism:

(1) rising global inequality, even within wealthy countries; (2) reduced wages and increased debt; (3) redistribution of profits from non-financial companies to the finance sector; (4) the growth of personal and financial insecurity, destruction of social capital and resulting rise in crime; and last but not least, (5) the relentless commodification of more aspects and components of social and biospheric life/life forms, such as culturally specific processes, healthcare systems, education systems and values, and the ethos of the caring professions. New frontiers of commodification include commercial surrogacy and the patenting of the DNA of indigenous peoples without consent.

In addition:

Structural acceleration in processes, underpinned most powerfully in recent decades by neoliberalism, that cause loss of biodiversity and adversely impinge on the health of populations and sustainability of the biosphere include: ‘(1) intensification of the exploitation of human beings, social processes, and nature for purposes of; (2) incremental dispossession of communities of their basic and local means of subsistence and livelihood; (3) acceleration in the turnover time of the production and sale of commodities to generate quicker accumulation of profits for firms and investors; and (4) restructuring or privatization of previously public institutions and public goods, including provisions for healthcare and education’.

Neoliberalism thus generates distortions within the system as ‘economic growth’ becomes ever more unsustainable through overconsumption of resources, with profit before people - siphoned off out of the economy into the pockets of the wealthy - whereby human rights becomes a selective process, usually favouring the privileged, especially within the context of the split between the north and the global south. Then there’s the belief that science and technology will provide the magic bullet to cure all our ills, whilst ignoring contradictory evidence. This leads to a process of dehumanisation. The following infographic outlines power structures and relations.

The negative impacts of neoliberalism is fuelling the rise of fascist elements:

which are emerging throughout the world in response to the global organic crisis and the inability of neoliberal leaderships to provide convincing exit strategies with credibility in the eyes of a majority of the population.

However there is also an emergence of leftist entities, with a focus on emancipation and collectivism, i.e. social democracy. Neoliberalism is thus cast as an extremist ideology, considered on a par with the sciences. There is absolutism in the belief:

The moral and political values that underpin such a paradigm include identification of humans as autonomous individuals with rights that can be used to foster their egoistical pursuit – largely through the endless consumerism that is required to reproduce the incessant demands for ever greater capitalist production.

Another slant on the issue is covered by the paper, Stateless Environmentalism: The Criticism of State by Eco-Anarchist Perspectives (2021), published in the International Journal for Critical Geographies.

Focusing on the role of the state in managing environmental issues, it notes:

nation-states have lost power in their capacity to unilaterally regulate important environmental dues and duties, given for instance the weakness shown under the influence of market institutions. Furthermore, they usually contribute to sponsor and promote private and national projects that inflict severe and non-reversible damages on environment, such as extractivism, hydropower dams, land grabbing and urban sprawl. This shows that environmental states do the management of environmental challenges through a double standard and commonly have a counterproductive effect. According to the above scenario, it would be difficult to support the argument that the State is an authorized power in order to face efficiently environmental issues.

In short, any responsibility by the state over environmental issues, as dictated by their actions and deferment to neoliberalism, undermines legitimacy. The paper therefore cautiously advocates an eco-anarchist approach as a possible critique to the status quo, considering the state ‘as a determinant driving force of the ecological crisis’. Such an approach would encompass the concepts of social ecology, liberation ecology, anarcho-primitivism, bioregionalism and deep ecology.

The notion of anarchism as chaotic is regarded as a misconception, as is the image of the State with order and organisation:

Anarchist ontology sees the State as an unnatural and alien polity when it is compared to the way in which human societies have organized themselves throughout their historical evolution. In fact, an essential pillar of anarchist utopia is the conception of a social organization in which there is no place for institutions and organizations that gather power and use it to exploit or oppress society.

A society approach could deal with environmental changes more effectively than inflexible bureaucratic institutions. Indeed any actions that states have taken to deal with serious adversity has been through the result of social pressure. Anarchists argue that the state has removed cooperative and collective elements within society:

There are internal necessities performed by the State, such as resource extraction, administration and coercive control from which society is excluded or reduced to mere passive individuals. This reinforces the thesis that there are statist interests beside the social ones, which are intentionally hermetic and hidden to the population (Trainer 2017).

As already noted, the State is an unnatural form, that society actually preceded the State. This is a slant to indigenous societies, which tend to be associated with a non-hierarchical and cooperative culture, with an intimate, emotional and respectful relationship with the environment. This becomes extended to the realisation that ecological systems aren’t ordered or centralised in the way a state is. It’s an interactive dynamic system that adapts to changes following the laws of nature in order to attain a level of equilibrium. This is the opposite of human activity which attempts to dominate nature and manipulate the laws of physics, which is impossible. The paper notes:

for eco-anarchists, the State is far to be a suitable structure of power to which delegate the management of Nature and environmental problems, given its size and design regarding the eco-social space under its domain. Thus, for bioregionalists, the State is a dysfunctional spatial configuration and the “typically large scale of the nation-state as a territorial unit, when combined with the centralized nature of the state as a decision-making body, ensures that it is insufficiently responsive to the idiosyncratic needs of specific ecosystems”.

An example of human disparity is the arbitrary and random political boundaries that exist between many states that rarely follow natural divisions. This is what differentiates bioregions from states. As noted above, whether modern societies could function at a bioregional level is open to debate. It would require a lot of planning, social and political restructuring. The use of technology could be contentious:

it would be intricate to undertake the role of technology in this transition, since this has been frequently associated to the exercise of bureaucratized power and to a vertical and linear way of managing problems: standardized procedures, instrumentalization of the use of Nature, dependency from green technologies to implement solutions, liberation of responsibilities to citizens and little initiative to reflection, education and household practices.

False Solutions and Total Failure

The studies covered above offer a useful theoretical and conceptual framework with which to build potential solutions to the climate crisis. But as thing’s stand, under the current system, nature has become a sacrifice zone, an issue that Greenpeace covers:

Sacrifice zones are geographical areas which are knowingly destroyed in the name of power and profit. They are generally ‘out of the way’ places, and the people who reside in them tend to be poor and lacking political power. This usually has something to do with race and/or class.

Typically these can include areas where large polluting industries are located, or entire countries such as Bangladesh, which is directly affected by rising sea levels and extreme weather. Sacrifice zones are generally the result of colonial impacts and neoliberal polices, driven by a white superiority complex.

Technological solutions are seen as the answer to the climate crisis. If technology created the problem, it can also provide the solution. Simple? This is where SG comes in, which effectively brings us round full circle. As the article notes:

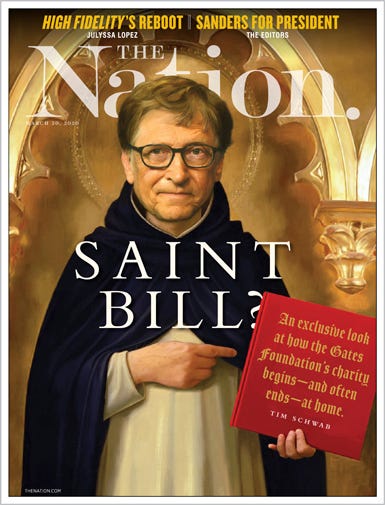

Often funded by the rich, white likes of Bill Gates, these extreme climate ‘solutions’ are gaining more and more attention – primarily from billionaires, big corps, oil giants and governments in the Global North. Their stance on solar geoengineering is unsurprising given that the alternative would involve addressing the roots of our climate problems, which also happen to be the source of their “success” (shock horror… it’s capitalism and white supremacy).

Given the uncertainty around such solutions, if they don’t work the results could be catastrophic. Not only would they waste time and money, they could also waste the planet, or perhaps more specifically, the sacrifice zones. To sum up:

As much as technological innovation will be an important factor in achieving a greener society, false solutions like geoengineering simply protect the status quo: inequality, exploitation, neo-colonialism and sacrifice zones.

Lets return to ARIA’s proposals for Exploring Options for Actively Cooling the Earth. The reasoning behind the plans to investigate SG is to ‘buy time’, because reducing greenhouse gas levels ‘may not happen fast enough to prevent the onset of tipping points’. The paper then explains what we’ve already known for nearly half a century. It then labours over the risks of SG processes, the ‘scope and scale of their side-effects’ and the ‘risks of unintended consequences’, and compares the risks of not taking action to cool the earth, with the risk of allowing catastrophic climate change to occur. The solution?:

we see a need for a programme that will accommodate small, controlled, geographically-confined outdoor experiments on approaches that may one day scale to help reduce global temperatures. These outdoor experiments are intended to answer critical scientific questions as to the practicality, measurability, controllability and likely (side-)effects of the proposed approaches that cannot be answered by other means.

The following infographic outlines the framework ARIA intends to follow.

Outdoor experiments will be small scale, which can be curtailed quickly should anomalies arise. Other guidelines include; operating within domestic and international law; Conducting transparent risk and impact assessments. Throughout the paper there’s a persistent commitment to transparency and taking an ethical approach, then this caveat cropped up (emphasis added):

Requiring that the results from the work that we fund (including negative results) are available in a publicly available, open-access form, unless such publication would be likely to lead to public harm.

This phrase appears three times within the paper. It’s contradictory (but see below).

ARIA will provide the funding for most of the initiatives, with the source coming from the government, or more specifically:

Created by an Act of Parliament, and sponsored by the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology, ARIA funds breakthrough R&D in underexplored areas to catalyse new paths to prosperity for the UK and the world.

As the Daily Sceptic reports, ARIA was originally the brainchild of Dominic Cummings, who courted controversy during the Covid pandemic and beyond. The idea was inspired by the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Centre (PARC). According to the article:

ARIA, as a quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation under the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, is a textbook case of government overreach. Unlike private firms, which innovate or die by market forces, quangos thrive on political cosiness and self-preservation. ARIA’s exemption from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, baked into the 2022 ARIA Act, cloaks its £800 million budget in opacity. With little public scrutiny, ARIA could fritter away millions on pet projects, eroding trust in a nation still smarting from procurement scandals during the Covid lockdowns.

OpenDemocracy reported on the decision to exempt ARIA from FOI requests. Quoting Tom Brake, from Unlock Democracy:

“The information that BEIS tried to keep out of the public domain reinforces what we already knew. The main justification the government has given for excluding ARIA from FOI is because, in their view, ARIA's activities will be of significant public interest and will trigger FOI requests which ARIA would struggle to handle.”

Perhaps this explains the sensitivity of publications that would likely lead to public harm.

So, who’s running the operation? The chair of the board is Matt Clifford:

Matt is the co-founder and Chair of Entrepreneur First (EF) and Vice Chair of the Advisory Board for the UK AI Safety Institute. In 2023, he served as the UK Prime Minister's Representative for the AI Safety Summit at Bletchley Park. Matt was awarded an MBE for services to business in 2016, and a CBE for services to AI in 2024.

Clifford’s area of expertise is artificial intelligence (AI). He is effectively a government spad (special adviser) on Hi Tech. He does though have his detractors as the Financial Times reports. In particular there are concerns that AI could be used for more sinister purposes e.g. bias and copyright infringements. Indeed (relative to ARIA):

Clifford has been an advocate for relaxing copyright restrictions to allow AI companies to mine data, text and images to train their algorithms.

Also noted was Clifford’s investment in medtech company Accurx, which has large NHS contracts and which has come under scrutiny concerning its domination over video consulting services.

Democracy for Sale delves into the AI controversy further. It notes:

In January, we reported that Clifford’s public register had not included interests in several AI businesses, including a £40 million AI investment fund run by Hakluyt, a firm with close Labour ties. At the time, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) refused to publish a full list of his financial interests.

Through an FOI request, it turns out that Clifford has investments in nearly 500 tech firms, most of which will benefit from the UK’s AI boom. EF holds stakes in 449 tech companies, ‘Despite his central role in shaping AI policy, these financial ties were not publicly disclosed.’ This has attracted criticisms of conflicts of interest. A lobbying entity called The Startup Coalition, linked to EF has been pushing for exemptions of AI developers from copyright law, assisted with funding from Big Tech, which includes Google. Clifford also has transatlantic connections:

Clifford helped establish the UK’s AI Safety Institute—recently rebranded the AI Security Institute, reportedly to align with the Trump White House’s AI approach. He is widely regarded as a respected expert in the field. Starmer accepted all 50 recommendations from his AI plan, published in January.

Suffice to say, there are concerns regarding Clifford’s influence.

Lets now examine SG from a scientific perspective. The paper Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non-use agreement (2022), is published by Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Climate change. It notes that Advocates of SG argue that efforts to tackle climate change have failed and that:

solar geoengineering could be used in the future either as a temporary measure to buy time to realize full decarbonization (“peak-shaving” of temperature increases) or as a failsafe to limit climate hazards in the event that decarbonization or carbon neutrality cannot be achieved in time.

But ‘the risks and efficacy of solar geoengineering are poorly understood’, making the important point that:

Current research is also often based on idealized modelling schemes and presumes facilitative politics that will be impossible to realize in today's fractious international order.

Also:

there are serious concerns about “locking in” solar geoengineering as an infrastructure and policy option as well as about militarization and security.

How such proposals could be effectively deployed within the current international political system is a key point of consideration. Global democratic decision-making would be difficult to implement. The global south in particular would be impacted, with its widespread poverty and inequality:

These global poor are extremely vulnerable to any change in their environment and threatened the most by any risks or side effects that might result from the deployment of solar geoengineering at planetary scale. Conversely, the global poor would also be the first to suffer from drastic climate change. Various researchers have argued that this suffering could be alleviated by solar geoengineering, leading some to postulate a moral obligation of industrialized countries to engage in solar geoengineering research to compensate for past and current greenhouse gas emissions. Yet one cannot achieve climate justice by addressing one aspect of justice and violating another.

It’s unlikely that the current world order could engage in effective political and democratic control over SG. Of particular note here was a UN resolution on SG that was blocked. As Scientific American reported, the US along with Saudi Arabia and Brazil, prevented the UNEP resolution from going forward, with the US insisting that any report on SG should fall within the remit of the IPCC. Micronesia raised the issue of impacts on the stratospheric ozone layer from SG as a possible unintended consequence.

Also the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) would have little influence on how SG would be implemented. Then there’s the potential for countries to directly challenge SG through counter geoengineering. The paper notes:

The United Nations Security Council has a mandate to act if it deems a situation to be a threat to international peace and security. Yet the Security Council, with five countries having permanent seats and veto rights, does not enjoy the global legitimacy to effectively regulate future global deployment of solar geoengineering technologies.

There’s no internationally based system to monitor the deployment of SG. In short, SG could take on a colonial dimension. It could also scupper genuine efforts to take action to curb CO2 emissions, which is nothing new:

Powerful industry interests, notably from the energy sector, have long invested in delaying stringent climate policies; seeking out technical alternatives such as carbon dioxide removal and sequestration; or denying the phenomenon of climate change altogether. The looming possibility of future solar geoengineering could become a powerful argument for energy companies and oil-dependent countries to further delay decarbonization policies. This risk is particularly high now, with a surge of countries announcing their intention to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 or earlier.

Any position against SG is simply following previous actions that banned dangerous technologies or substances - basically an International Non-Use Agreement on SG - as the paper outlines:

The international community has a rich history of international restrictions and moratoria over activities and technologies judged to be too dangerous, undesirable, and risky. For example, governments have issued a moratorium on mining in Antarctica and have banned the emission of substances that deplete the ozone layer. Various nuclear activities, the dumping of most types of waste at sea, some uses of outer space, the production of many harmful chemicals, exports of hazardous waste, and so forth are also banned. Notably, international agreements have already adopted measures to restrict some types of geoengineering, such as fertilizing parts of the oceans with iron filings to increase their biological productivity and carbon dioxide uptake (under the London Protocol on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter and under the Convention on Biological Diversity).

The paper Activism and Neoliberalism: Two Sides of Geoengineering Discourse (2018), published in Capitalism Nature Socialism, focuses on the contrasting discourses of environmental neoliberalism and ecological egalitarianism, through the lens of Critical Discourse Analysis. The latter tends to be upheld by environmental groups, whilst the former is the domain of conservative think tanks such as the Cato Institute, funded by the likes of Bill Gates (more about him later). The paper notes that a Royal Society 2009 report, kickstarted the debate on SG. This prompted the involvement of The Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) (see below).

The paper notes that some of the high profile scientists engaged in research haven’t endorsed the rolling out of SG, although small scale testing in the future isn’t ruled out. It indicates that SG will be driven by neoliberal processes. The logic behind this is that it will serve the market more effectively if nothing is done to curb emissions whilst fossil fuel production continues unabated. Then when the market is ready and the process is financially sound, SG can be rolled out under the notion of an innovative process through creative destruction - a concept outlined by Schumpeter, which I cover here.

In short, SG will magically solve the climate crisis allowing the free market to deliver, as it always does… . This is largely driven by the power of the entrepreneur, typically billionaires, who have a lot of financial clout and influence. Within this context, this has given rise to green capitalism, which emphasises the commodification of nature, where ecosystems and biological diversity has market value and can serve the economy. This:

is consistent with Marx’s “discussion of the bourgeois subject’s relentless drive to reproduce and expand capital accumulation via anarchic, entrepreneurial investment,” and is laden with a kind of techno-utopianism that places faith in technologies to solve complex problems overseen by this new “entrepreneurial man.”

In this respect, the paper notes how Richard Branson introduced the Virgin Earth Challenge, worth $25 million to anyone who could produce a design:

able to remove “significant volumes of anthropogenic, atmospheric GHGs each year for at least 10 years” on a net basis, which “should be scalable to a significant size in order to meet the informal removal target of 1 billion tonnes of carbon-equivalent per year”.

There were no takers and the ‘Challenge’ is no longer active.

The inimitable Bill Gates has also provided funding to support projects, including several million dollars to Harvard University to engage in SRM research (see below). Branson and Gates characterise:

the perpetuation of the neoliberal construct of the individual as a self-governing and empowered entity best placed to use his, and it is usually a “his,” entrepreneurial perspicacity to solve the climate problem.

The paper discusses opponents of geoengineering, outlining many of the issues covered above. It notes how the counter-argument is well organised and researched. It mentions Ulrich Beck’s risk society, where technological developments, e.g. nuclear power and biotechnology, create new risks and uncertainty. Also noted is the leap manifesto, initiated by Naomi Klein:

and backed by a host of NGOs, academics, unions, celebrities, legal organizations and advocacy groups, makes use of this ecologically resonant corollary by calling for an economy in which “[c]aring for one another and caring for the planet could … [become] the economy’s fastest growing sectors,” in which respecting indigenous knowledge that “bind[s] us to share the land” is the norm, and where “localized and ecologically based agriculture systems” dominate.

Also outlined is the slippery slope argument, which postulates that any small scale trials will represent the thin edge of the wedge, driving large-scale political and corporate deployment, thus making it difficult to refocus on the need to cut emissions in wealthy countries.

The paper, Profit-seeking solar geoengineering exemplifies broader risks of market-based climate governance, is published in Earth System Governance. It takes the position that:

solar geoengineering is emerging within and perpetuating a neoliberal climate framework where direct “climate cooling” is poised to become just another ineffective climate commodity.

It cites the example of US based company Make Sunsets, which is sending balloons into the atmosphere filled with sulphur dioxide, marketing it as cooling credits to engage with the voluntary carbon offset market. This is a predictable manifestation of neoliberal market driven climate policies, along with seeding the oceans with iron to increase plankton growth and sequester CO2, but restrictions were imposed, which have not yet been applied to atmospheric SG. A parallel here is carbon offsetting - not SG, but a classic example of a market driven initiative, covered here.

In another example:

in 2018 the idea of ‘radiative forcing credits’ was introduced to the International Standards Organization (ISO) by SCS Global Services and First Environment, two US-based companies that specialize in sustainability certifications. Their goal was to create a standard that would account for all forms of climate forcing, including negative climate forcers like reflectivity. …This proposed new standard was met with resistance, primarily from European organizations who feared that such a standard would legitimize solar geoengineering projects and undermine existing metrics for emissions accounting. The draft standard was eventually downgraded to a technical document without any advice-giving character.

The paper importantly considers the domination of neoliberal policies with the difficulties of implementing effective oversight:

Powerful business lobbies fund and advocate not only for specific interventions, but also a whole framework of neoliberal political ideology, and policymakers are hemmed in by market-based thinking, modelling and policy making.

In short, government oversight is wholly inadequate and that’s unlikely to change under the current system. Much of this is dominated by Silicon Valley culture, who’s big tech approach to innovation has been described as a theology:

or an unfounded systematic belief “that technologies should be launched on the market, exempt from any regulation and intervention … the beneficiaries of these technologies are autonomous, rational individuals who exercise their rights and liberties. Thus, improvement of the species will be achieved via countless individual decisions, which will lead to collective benefit”.

The following infographic outlines the general picture.

Of considerable concern is SG’s links to the defence industry, in which ‘the U.S. military has a strategic interest in solar geoengineering, as U.S. hegemony is predicated on expanding fossil fuels, but the military deems climate change a threat to national security’. Then there is the expanding energy requirements of AI growth. The paper sums up:

venture investors replace scientific founders with business strategists, and demand business models that maximize profits rather than environmental gain.

The Neoliberal Philanthropist

In 1975, Bill Gates, along with Paul Allen, founded Microsoft. The company took off after going public in 1986. The following year, Gates became the youngest ever billionaire at 31. Microsoft quickly capitalised on the emerging PC market and internet expansion. The launch of Windows 95 in August 1995 gave Microsoft a market lead. The platform included the online service MSN and the Internet Explorer browser. Up until then, users depended on separate browsers. Netscape, which dominated the browser market was eventually forced out of business. Indeed the whole debacle became the centre of a major law suit, where Microsoft was accused of monopolising the software business. It wasn’t the first controversy Microsoft faced and it certainly wasn’t the last.

In 2000, Gates stepped down from his CEO role. Following this, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was formed. Since his divorce from Belinda in 2021, it has become generally known as the Gates Foundation. The GF has a broad portfolio. Gates was inspired by the Rockefeller Foundation, which I cover here.

GF has become associated with Philanthrocapitalism. In 2011, Huffpost reported on the association with the former notorious Monsanto Corporation. The GF had an investment of $23.1 million in Monsanto stock. It had set up an initiative called an Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). Despite initially denying pushing GMOs (genetically modified organisms), it became apparent that funding through AGRA was being used to develop and promote genetically modified seeds. The US government also had a stake, via the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which just happened to be headed by former Gates employee Rajiv Shah. This was seen as a trojan horse to open up the GM market in Africa. Monitoring AGRA is AGRA Watch, part of the Community Alliance for Global Justice, which challenges ‘the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s questionable agricultural programs in Africa’. In 2024, African faith leaders demanded reparations from the GF. AGRA Watch notes:

“The Green Revolution is a mirage; it’s colonisation in disguise promoting capitalism from the global North to continue controlling our food systems, environment, well-being, and livelihoods,” Sarah Haloba from the Zambian Governance Foundation, told investigators.

In 2016, Gates announced to the world ‘We Need a Miracle’, regarding climate change. In an interview with Bloomberg he stated:

Geoengineering is, at best, a backup strategy to buy ourselves time, if we don't move quickly enough and things like the ice melting and methane release are happening in a nonlinear way that we don't expect. I support research on geoengineering and a dialogue on geoengineering. But it really is like a fire extinguisher that puts the flames out for decades as opposed to a real solution.

As part of the research, Gates set up Breakthrough Energy. On its website it claims:

The only way to avoid the worst impacts of climate change is to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions from 51 billion tons a year, where they are now, to net-zero—and we need to do it by 2050. That means we need unprecedented technological transformations in almost every sector of modern life.

At Breakthrough Energy, we’re accelerating this transformation by supporting cutting-edge research and development, investing in companies that turn green ideas into clean products, and advocating for policies that speed innovation from lab to market. Through investment vehicles, philanthropic programs, policy and advocacy efforts, and other initiatives, Breakthrough Energy works with a global network of partners to accelerate the technologies we need to build a carbon-free economy.

In other words, technology will solve the climate crisis within the free market. BE looks a bit like AGRA’s twin.

An article from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists gives a detailed and broad overview of the issues related to SG. It makes the important point that SG would have no effect on other related impacts such as ocean acidification.

It notes that David Keith, who was involved in research at Harvard University has now been hired by the University of Chicago, due to problems getting experimentation off the ground at Harvard. However Chicago’s approach raised eyebrows as the most of the people involved in the research - climate systems engineering - were linked to the economics department. And just to underline the mentality behind the fossil fuel industry, Carbon Engineering, a company founded by Keith that focused on carbon removal, was acquired by Occidental:

Occidental will use the captured carbon dioxide, at least in part, to pressurize oil fields and extract more oil from them. The industry considers the technology a kind of lifeline: “If it’s produced in the way that I’m talking about, there’s no reason not to produce oil and gas forever,” Occidental CEO Vicki Hollub told NPR. (Keith has had no legal involvement with Carbon Engineering since the sale was completed.)

The article compares SG with the 2008 financial collapse. It could create ‘an ever-increasing “climate debt” that carbon dioxide removal may or may not ever be able to pay back’. If implemented on a large scale it could become addictive, locking it in as a permanent long term commitment, with unknown consequences.

Michael Mann, a noted climate scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, has raised concerns about figures like Bill Gates, ‘for funding technological solutions to climate change while downplaying or rejecting more effective political solutions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions’. The link points to an article from Varsity - How the cult of Bill Gates is leading us towards a climate disaster.

Gates has become something of an icon - or perhaps idol might be more appropriate. In 2021, he decided to weigh in on the climate crisis with a book, titled How to Avoid a Climate Disaster. 20 years ago it was very different. Varsity notes his reason for stepping down from the helm at Microsoft and forming the GF. He:

found himself in the middle of a lengthy federal lawsuit against Microsoft, which had a disastrous impact on his public perception. His videotaped testimony in particular, “was a disaster.” It was also at this time that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) was founded, the motives for which were widely questioned.

His reputation recovered though, with a little help from the media outlets he donated to, which included the likes of the BBC and the Guardian. Of course no good noeliberalist’s portfolio would ever be complete without tax avoidance.

Gates has also been critical of climate activism. We wonder why!:

It’s evident that Gates has the most to lose from more radical solutions to the climate crisis, which attempt to address our capitalist society’s obsession with economic growth, its ignorance of ecological boundaries, and its inherent inequalities. Gates does not want a new normal. He wants very much the same normal - just with less carbon emissions.

He even came up with the nonsensical proposal for replacing aviation fuels with biofuels.

So there you have it. The gospel according to Bill Gates.

But there is still the ARIA controversy here in the UK. As noted above, NERC will also be involved in funding SRM research. The website carries a disclaimer (emphasis added):

This is distinct from the work of Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA). The NERC programme is focused on innovative climate modelling, while ARIA’s programme is focused on researching new and existing technologies for climate and weather management. The NERC programme has been developed independently of ARIA’s work in this space. However, NERC will continue to engage with ARIA and other government bodies as this work progresses, as is routine in applied research.

However NERC has its own shady track record. An 2015 investigation by Greenpeace revealed that NERC had received funding from Shell and other big oil companies:

Funds from Shell have gone to fund each of NERC’s research centres: the British Antarctic Survey; British Geological Survey; Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, and National Oceanography Centre, according to information provided under FOI.

Also NERC was involved in discussions with oil representatives on how to effectively expand North sea oil and gas exploration. In a statement to Greenpeace NERC noted:

“The entire funding from the oil and gas sector to NERC and its research centres represents only two per cent of funding, so your article is leaning towards sensationalism rather than accuracy; we’re disappointed at the lack of support from the research journalism community.”

But there’s more. DeSmog UK reported (2015) on a ‘Frackademia' report, which revealed links between the UK Government, universities, and the fracking industry. It turned out that NERC was involved in creating and funding so-called Centres for Doctoral Training (CDTs) (aimed at doctoral students). NERC:

established the CDT in oil and gas in 2013 to train the next generation of geoscientific and environmental researchers in this field.

This begged the question as to why NERC was providing funding to an industry that will cause environmental damage? Indeed that question resonates today.

The fact is we have universally and utterly failed to reign in carbon emissions. That includes civil society, who’s actions have been ignored by decision makers. Just look at this graph closely. It hasn’t changed a bit since records began back in 1958.

Indeed in an article from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, it has been confirmed that CO2 emissions are actually accelerating. Once the graph starts levelling out, then we can convince ourselves we’re tackling the climate crisis. But that’s unlikely anytime soon. It’s also unlikely that tinkering with the climate will solve the plethora of environmental problems we face. We are destroying our planet full stop. If it wasn’t the climate it would be something else. What we’re facing is a perfect storm. And the changes are already happening. Unprecedented collective action is required. But don’t expect anything from the politicians or corporate interests, wedded to the neoliberal cult.