Mediterranean Gas — The Latest Resource Colonialism

The Gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean has become the scene of the latest resource grab in the Middle East

In the Eastern Mediterranean, the discovery of substantial reserves of natural gas (and oil) in an area known as the Levantine Basin (map below), could elevate Israel’s position as a major Middle Eastern energy producer.

On March 30, 2013 Israel began production in the Tamar field. The Tamar and Dalit fields could supply Israel with gas for two decades. The larger Leviathan field is estimated to hold 18 trillion cubic feet of gas. Tamar could contribute about 1 percent to Israel’s gross domestic product, according to the Bank of Israel.

Background

A paper from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), East Mediterranean Gas: what kind of a game-changer? (2012), delves into the background. 1999 saw a major breakthrough with the discovery of two gas fields, the Noa and Mari-B fields, with potential reserves of 32 Billion cubic meters (Bcm). The key players involved in the initial exploration was US based Noble Energy and Israel’s Delek Group, under a consortium known as Yam Tethys. In 2000, the British Gas (BG) Group discovered the Gaza Marine field, located 36 km off the Gaza shore, with a similar potential as the other fields. In 2002, the Palestinian Authority (PA), which had jurisdiction over Gaza, agreed to a four-year development plan to develop the Gaza field and build a pipeline, with the Lebanese Consolidated Construction International Company (CCC, 30%), the Palestinian Investment Fund (10%), and the BG Group (60%) in a partnership. However:

negotiations between BG and Israel broke down following Israeli demands to control gas flows from Gaza Marine, and revenues to the PA under any prospective agreement, leaving the field undeveloped until today and Gaza’s wider offshore area under-explored.

Major discoveries in 2009 and 2010, opened up the area further, with a total potential of up to 810 Bcm. These include the two largest fields, the Leviathan and the Tamar. By comparison, the total natural gas potential discovered in the north sea in the 1960s amounted to around 865 Bcm. The potential reserves in the Levant Basin could increase through time as other areas such as the North sea did. Indeed the US Geological Survey estimates that the Basin may hold up to 3.45 Tcm of gas. Cyprus, Syria and Lebanon was also engaged in offshore exploration, with Lebanon poised to carve out the largest share along with Israel. Of course the fly in the ointment here is the geopolitical situation in the region, now exasperated with the assault in Gaza. Firstly, there’s the Greece/Turkey division on Cyprus, which sits to the north west of the gas fields. Which side will claim Cyprus’ share of the spoils? Syria also has a claim, but a decade of instability and conflict has created uncertainty, particularly with the collapse of the Assad regime. Then there’s the situation with Lebanon, which I’ll cover later. But most important was Gaza’s claim to the Gaza Marine field, discovered in 2000, which could have provided a potential revenue of at least US$1 billion to the Palestinian Authority, which took control of Gaza following the Oslo Accords. As an article from TomDispatch outlines, the PA would have been responsible for territorial waters off the coast of Gaza. This would have had an important bearing on a Palestinian claim to offshore natural gas.

In 1999, the PA established the deal with BG. What followed was some familiar wheeling and dealing from Israel. BG would finance and manage the development, in exchange for 90% of revenue:

With an already functioning natural gas industry, Egypt agreed to be the on-shore hub and transit point for the gas. The Palestinians were to receive 10% of the revenues (estimated at about a billion dollars in total) and were guaranteed access to enough gas to meet their needs.

But Israel had different ideas. Facing economic and energy woes, Prime Minister Ehud Barak took control of Gazan coastal waters and cancelled the deal with BG:

He demanded that Israel, not Egypt, receive the Gaza gas and that it also control all the revenues destined for the Palestinians — to prevent the money from being used to “fund terror.”

That effectively buried the Oslo Accords. The Israeli decision led to an intervention from Tony Blair, who proposed a competitive deal in 2007, but Israel’s reluctance was reinforced by the Hamas election victory in 2006. Israel rejected everything on the table and instead subjected Gaza to an ongoing blockade. Israel’s long term plan was to extract the gas from Coastal waters off Gaza, once Hamas was out of the way:

As former Israel Defense Forces commander and current Foreign Minister Moshe Ya’alon explained, “Hamas… has confirmed its capability to bomb Israel’s strategic gas and electricity installations… It is clear that, without an overall military operation to uproot Hamas control of Gaza, no drilling work can take place without the consent of the radical Islamic movement.”

The solution to the problem? Operation Cast Lead. Unfortunately for Israel the 22 day offensive launched late 2008 did not achieve its aims. The stalemate over gas extraction remained. Enter new Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who came to power in 2009. Israel’s energy crisis was about to intensify as the Arab Spring uprisings impacted gas supplies to Israel. This led to major protests in the country. Not surprisingly, Israel’s attention was immediately drawn to the Mediterranean:

As it happened, however, the Netanyahu regime also inherited a potentially permanent solution to the problem. An immense field of recoverable natural gas was discovered in the Levantine Basin, a mainly offshore formation under the eastern Mediterranean. Israeli officials immediately asserted that “most” of the newly confirmed gas reserves lay “within Israeli territory.” In doing so, they ignored contrary claims by Lebanon, Syria, Cyprus, and the Palestinians.

By disregarding legitimate claims from other countries in the region, Israel did what it usually does - it pushed it’s weight around. As a result, Lebanon became the first flash point after Israel began exploratory drilling in disputed waters. This led to a threat of attack from Lebanon if Israel began production in the area. Israel had the technical, military and commercial backing though to push its agenda through, Lebanon didn’t. So Israel pushed ahead regardless. It was around this time that Israel implemented the US funded iron dome system to protect against attacks from Hamas and Hezbollah, whilst also expanding its naval presence in the area. But Lebanon was not deterred:

In 2013, Lebanon made a move of its own. It began negotiating with Russia. The goal was to get that country’s gas firms to develop Lebanese offshore claims, while the formidable Russian navy would lend a hand with the “long-running territorial dispute with Israel.”

By early 2015, it was stalemate again. Israel managed to bring onstream two smaller fields, but the main prize was stalled “in light of the security situation.” U.S. contractor Noble Energy, who had been hired by Israel to exploit the area, pulled out of the deal, citing security concerns.

But it wasn’t just Lebanon that was courting Russia. With the the country in free-fall as civil war erupted, Syria, was at a crossroads:

The regime of Bashar al-Assad, facing a ferocious threat from various groups of jihadists, survived in part by negotiating massive military support from Russia in exchange for a 25-year contract to develop Syria’s claims to that Levantine gas field. Included in the deal was a major expansion of the Russian naval base at the port city of Tartus, ensuring a far larger Russian naval presence in the Levantine Basin.

However, Israel was about to engage in some illicit gambling. There was potential oil reserves in the occupied Syrian territory of the Golan Heights. Israel gave U.S.-based Genie Energy Corporation exploration rights:

Facing a potential violation of international law, the Netanyahu government invoked, as the basis for its acts, an Israeli court ruling that the exploitation of natural resources in occupied territories was legal. At the same time, to prepare for the inevitable battle with whichever faction or factions emerged triumphant from the Syrian civil war, it began shoring up the Israeli military presence in the Golan Heights.

Meanwhile the Palestinians were still prepared to push for their share in the offshore gas, rejecting Israel’s moves to sideline them. As a result:

The Palestinian Authority then followed the lead of the Lebanese, Syrians, and Turkish Cypriots, and in late 2013 signed an “exploration concession” with Gazprom, the huge Russian natural gas company. As with Lebanon and Syria, the Russian Navy loomed as a potential deterrent to Israeli interference.

With the energy crisis in Israel causing chaos with widespread blackouts, Israel had had enough of Palestinian obstruction. The Russian deal was the last straw:

With Gazprom’s move to develop the Palestinian-claimed gas deposits on the horizon, the Israelis launched their fifth military effort to force Palestinian acquiescence, Operation Protective Edge. It had two major hydrocarbon-related goals: to deter Palestinian-Russian plans and to finally eliminate the Gazan rocket systems.

A Guardian article from Nafeez Ahmed, just as Protective Edge was launched, elaborates on the issue. He cites IDF chief of staff Moshe Ya'alon, before Cast Lead took place:

"Proceeds of a Palestinian gas sale to Israel would likely not trickle down to help an impoverished Palestinian public. Rather, based on Israel's past experience, the proceeds will likely serve to fund further terror attacks against Israel…

A gas transaction with the Palestinian Authority [PA] will, by definition, involve Hamas. Hamas will either benefit from the royalties or it will sabotage the project and launch attacks against Fatah, the gas installations, Israel – or all three… It is clear that without an overall military operation to uproot Hamas control of Gaza, no drilling work can take place without the consent of the radical Islamic movement."

This then was the background to the 2014 attack on Gaza. As Ahmed notes:

According to Anais Antreasyan in the University of California's Journal of Palestine Studies, the most respected English language journal devoted to the Arab-Israeli conflict, Israel's stranglehold over Gaza has been designed to make "Palestinian access to the Marine-1 and Marine-2 gas wells impossible."

Following publication of this article, Ahmed was pushed out of the Guardian, settling the argument about the Guardian’s faux liberal status, as Jonathan Cook explained in his blog. Ahmed covered the background to the story in his own subsequent piece. I highlight this because of the distorted media coverage of Israel’s atrocities, and what can happen when journalists don’t participate in the corporate media merry-go-round.

A leaked report at the time outlined that Israel had overestimated the reserves of gas available, and that ‘Israel cannot simultaneously export gas and retain sufficient quantities to meet its domestic needs.’ Some of the reserves may not be commercially recoverable.

It’s all about the oil

What’s happening offshore in the Eastern Mediterranean isn’t new. Indeed even before the outbreak of World War 1, the Middle East became a geopolitical beachhead for the colonial powers. In the early 20th century, Britain’s navy began the transition over to oil. Britain’s initial foothold in the Middle East was to safeguard its empire. The key was the Suez Canal, a vital gateway to Asia and the British presence in India. This was consolidated with the British occupation of Egypt in 1882. An important stepping stone to a colonial foothold in the middle east was the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907, also known as the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia. It provided a pivot against the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. The agreement ended a dispute over Persia between Russia and Britain, which secured Russian influence in North Persia, with the British establishing a sphere of influence in Southern Persia. The agreement though went through without the knowledge of the Persians, sowing the seeds of future Iranian nationalism and anti-western sentiment. This also ensured access to the Persian Gulf, a vital trading conduit to this day.

The book Moguls and Mandarins: Oil, Imperialism and the Middle East in British Foreign Policy 1900-1940, goes into the background of how oil became such a vital commodity at the turn of the 20th century. The British presence in the Middle East at that time was primarily strategic, using political influence through commerce and trade. Britain was very conscious of the emerging power of Germany posing a threat, particularly with a plan to construct a railway from Baghdad to Berlin. German influence could impact the British and Indian share of around 80% of the total trade of the Persian Gulf. As such, shipping was also vital, with Britain and India accounting for around 85%.

Oil quickly became a key commodity. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), a British company, was founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia. Prospecting began in 1901, through the direction and funding from William Knox D'Arcy, a British-Australian businessman and one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Persia, who negotiated a deal with the Shah of Persia, with some diplomatic help from the British Government. Oil was eventually struck in 1908. In 1914, the British Government purchased a 51% shareholding in the APOC:

By this action the government obtained a financial interest in the Company and a controlling voice in its affairs. At the same time the government secured direct control over one of its sources of oil fuel for the Royal Navy. Finally, it acquired a material stake in a remote and foreign country whose strategic position was vital for the containment of those rival Great Powers, Russia and Germany, whose expansionist aims appeared to threaten the heart of Britain’s Empire, India.

This move was prescient, coming as it did on the eve of World War 1. By this time, Winston Churchill had become the First Lord of the Admiralty. He followed his predecessor in pushing for the conversion of coal to oil on naval ships. The APOC deal would ensure a cheap supply of oil for Britain, especially during war time, whilst holding a monopoly concession in Central and Southern Persia. Neighbouring Mesopotamia (now Iraq) was also an area under consideration. But there was competition there from Royal Dutch-Shell, which was influenced by Turkish interests:

Now Shell was trying to obtain the Mesopotamian concession and if this effort succeeded, Shell, through the Turkish Petroleum Company, would start a price war in the Middle East market and force the Anglo-Persian to merge that way. Thereafter the group would force up the price of oil and open up this potentially vast source of supply only gradually. If the Anglo-Persian was in danger so also, Greenway pointed out, was the Royal Navy and, indeed, the British Empire itself.

APOCs managing director Charles Greenway had laboured the point to the Government. This was a threat to British control in the region. But there was an irony here. The British had a 40% stake in Shell, with the Dutch holding 60%. However:

Shell was registered and domiciled in London and had a majority of British directors on its board. Shell considered itself British; its Anglo-Persian rival and the British government considered it Dutch, an opinion carrying the additional implication that Holland and therefore its international companies were subject to strong German influence.

After a protracted period of negotiation to find a solution to the issues facing APOC, the Admiralty agreed to take a stake in APOC. This became a British Government backed stake, which secured its oversight of the company, providing the finance for its share. There was a lot of criticism of the deal, but that subsided with the outbreak of war. It should be noted here that this deal, was not going to set a precedent for the future.

After the war, Britain and France dominated the jostling and partitioning of the Middle East, as the Mandate system was brought in, with commercial interests paramount, especially in the oil fields. Further discoveries were made in the region.

In 1928, another important milestone took place. The Red Line Agreement (RLA) was a deal was struck between British and French oil companies. It also brought US interests into the picture. It had its roots in the formation of the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) in 1912:

The TPC was formed as a joint venture between Royal Dutch/Shell, the Deutsche Bank, and the Turkish National Bank, in order to promote oil exploration and production within the Ottoman Empire. In March 1914, however, the British Government, which controlled the Turkish National Bank, managed to have its shares within the TPC transferred to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. The following June, the Ottoman Grand Vizier promised an oil concession to the reconstituted TPC to develop oil fields within the Ottoman provinces of Baghdad and Mosul.

The US was seeking to penetrate into the Middle East market at the end of the war, but the San Remo Oil Agreement, at the San Remo Conference of 1920, excluded US oil companies. But the US Government was determined its expanding oil interests would not be excluded. Its response was the passing of ‘the Mineral Leasing Act in February of 1920, which denied drilling rights on publicly-owned land in the United States to any foreign company whose parent government discriminated against American businesses.’ The RLA was the response, drawn up to accommodate US interests by incorporating them within what was effectively a TPC cartel, that expanded exploration in an area covering Iran and Iraq.

The US foothold

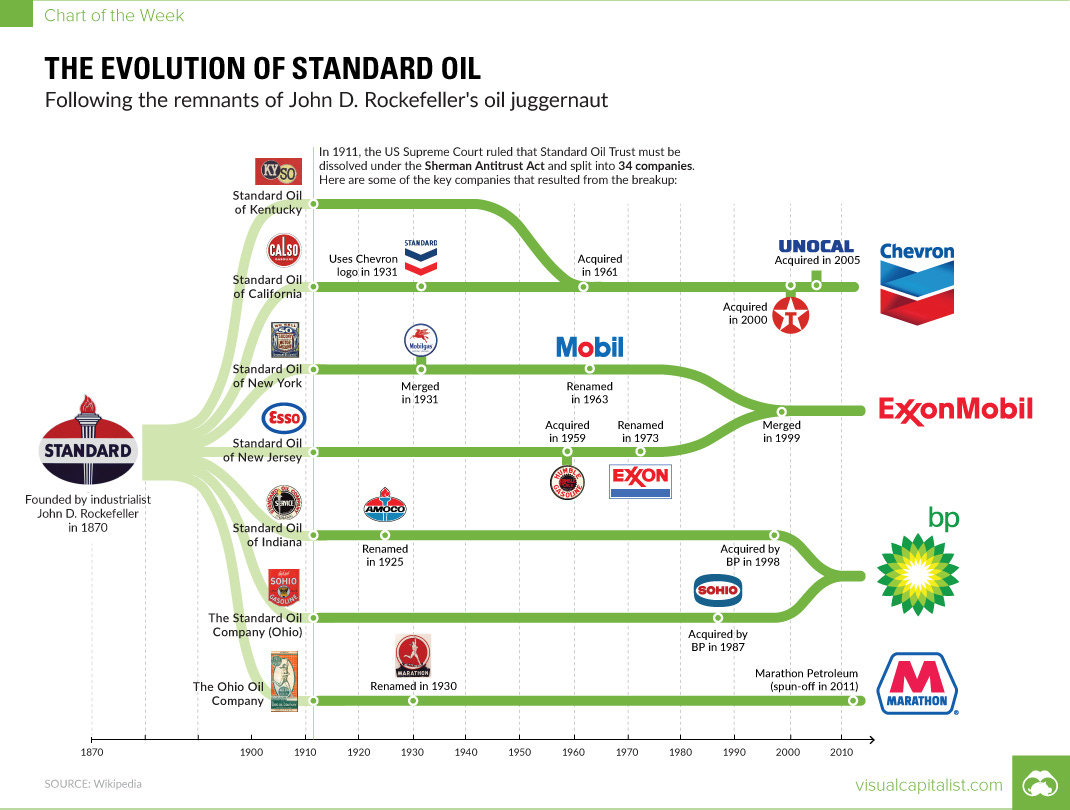

In 1870 the Standard Oil Company (Ohio) was founded by John D. Rockefeller, one of the richest people of all time and founder of the Rockefeller Foundation. This was before the emergence of the internal combustion engine. Initially the company grew in stature by buying out competitors and shutting down inefficient operations. Linked into an oil-pipe network, Standard could easily transport its product around the country and began to expand rapidly. To circumvent local state laws restricting national corporate expansion, the company quietly established a network of trusts. By 1904, Standard Oil controlled 91% of oil refinement and 85% of final sales in the US. By this time, the transportation sector was emerging, particularly with the development of the car industry.

The book Crude capitalism: oil, corporate power, and the making of the world market, explores the background of the rise of big oil in the US, revolving around the foundation of the Standard Oil Company. In the early days, the primary product from oil was kerosene, which was used for lamps and lighting. There was a major problem with the nascent US oil industry though. The market was unregulated and uncontrollable. It was a free for all as a mad rush ensured to capitalise on what became a volatile market due to overproduction. This is where Standard came in. If the means of production could be controlled and proper infrastructure used to channel the oil to refineries and finally to the customer, this would generate a balanced coordinated system. The book notes how:

Standard’s power emerged through a careful strategy of infrastructural control. This included buying up pipelines that connected oil fields to railroads, colluding with the railroad industry to obtain favourable rates for transporting crude, and taking ownership of virtually all downstream refineries that converted crude oil into kerosene.

Also the trustee system it set up to get round state restrictions was covert and secret. On the surface, it didn’t exist. Standard’s wider approach through its vertically integrated structure would set the benchmark for the future oil industry.

Standard’s business practises attracted suspicion and criticism. As a result, anti trust regulation emerged. Standard then broke up into individual but connected companies that bore the name of the state it operated in. But Standard still remained under scrutiny. The state of New Jersey came to the rescue, effectively becoming business friendly and creating legislation that would allow business to do ‘just as business pleases’, anywhere in the country. The result was that this allowed Standard:

to reorganise all the company’s affiliate firms under the umbrella of a single holding company, Standard Oil Co. New Jersey (SONJ). With this move, the twenty large Standard firms that had superseded the trust were now transformed into subsidiaries of SONJ. By absorbing these twenty companies and their affiliates, SONJ sat atop an empire consisting of about seventy firms in total, stretching across the US, Canada, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and several European countries.

Standard’s innovative approach marked the beginnings of a symbiotic relationship between oil, finance, and political power. These approaches extended to the international market. But with new discoveries at home, especially in Texas with its huge newly discovered potential and anti trust approach to Standard, competition had emerged. Meanwhile the market was changing, with the gradual transition towards fuel oil at the turn of the century and related markets. With competition and changing markets impacting Standard’s domination, its fortunes changed dramatically:

The final blow to the company came with a 1911 Supreme Court decision that found Standard guilty of violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, despite its attempts to reorganise itself in New Jersey, and ordering that it be broken up into thirty-four separate firms. Nonetheless, the formal end of the Standard empire did little to erode the wealth of the Rockefeller family. The assets of Standard were distributed back to their original shareholders, leaving dominant ownership across the now independent companies in the hands of John D. Rockefeller, who became the richest person in the world as a result of the decision.

Out of the firms that had emerged from Standard, four would later give birth to oil giants that would come to dominate the global landscape; Exxon and Mobil, who would eventually merge themselves into ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Standard Oil of Indiana, later merged with BP - itself the former APOC. The world was changing, and the outbreak of war would accelerate that change.

As with in Britain, the US had also decided to transition its Naval fleet over to oil prior to the war. After the outbreak of war, many new technologies were deployed that depended on oil fuel, such as tanks, submarines, and aircraft. War had been transformed into something that was ‘machine-like … an industry of professionalized human slaughter’. Oil:

tied the power of US oil firms to the deepening global war economy. From this point onwards, militarism would become a principal driver of oil consumption; indeed, today, the largest single institutional consumer of oil on the planet – and thus the largest institutional source of carbon emissions – is the US military.

After the war, the American Petroleum Institute (API) was formed in 1919. The war had set the scene for:

US oil policymaking to this day. All of this was further reinforced by the ‘revolving door’ between oil company management and US politicians. These entanglements of American politics and the private business of oil would deepen and expand over subsequent decades, with profound implications for the future trajectories of world oil.

I’ve covered the API in previous articles. This article from DeSmog outlines the chequered background of the API.

Personal transport expanded rapidly during the interwar years, so much so that the API noted in 1936:

that while ‘George Washington could travel no faster than Julius Caesar, and Caesar no faster than Solomon’, the US public had gone from ‘30 miles a day to 300 miles an hour … all within the last quarter of a century’.

Resulting from which the car industry had become a powerful player. But the major oil interests still had to find their footing on the international markets, despite a rapidly growing domestic market. The Middle east would eventually become a major focal point for US (and global) oil interests.

After the war, the US economy remained relatively stable. It was able to provide finance to war torn Europe. In the process, Wall St emerged as a potent financial centre that would rival London. Despite this though, the colonial powers still maintained their control. As such, the emergence of considerable oil resources in the Middle East would be of vital importance towards economic recovery. Shell and APOC were in pole position to reap the benefits of the expected oil bonanza.

The war had had a dramatic impact on the Middle East, revolving around the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent arbitrary redrawing of borders by colonial powers, all eyeing up oil resources. As the books notes:

While the region was not yet a major oil producer, it was keenly recognised that substantial reserves existed across Iran and the former Ottoman territories. Britain, in particular, placed utmost strategic priority on gaining dominance over these areas. The goal of British oil policy, according to Winston Churchill, was to become ‘the owners, or at any rate the controllers at the source, of at least a proportion of the supply of natural oil which we require … and to draw our oil supply, so far as possible, from sources under British control or British influence’.

Indeed Britain had immense influence in an area that included much of Iran, Egypt, Kuwait, and the Arabian Peninsula. The Sykes–Picot Agreement secured what is now Jordan, Palestine, and Iraq. As such, Britain had control of most of the export infrastructure in the area.

Given the US role in the war and the increasing domination of US oil companies in the global market, the US put pressure on Britain and other colonial countries for access to the Middle East market. This finally culminated in the RLA. Following this, the TPC became the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC). The agreement brought in the US companies under a consortium called the Near East Development Corporation, through the newly formed IPC. This gave the NEDC a vital foothold in Iraq, finding favour with Britain. It was:

through partnering with Britain as the colonial power in Iraq that US firms were able to enter Middle Eastern oil production for the first time.

The IPC agreement signalled a growing convergence between British and US interests at the global level. For Britain, this alliance helped guarantee the stable supply of oil – whether from the US in times of peace, or the Middle East in times of war. Additionally, IPC’s distinct corporate structure contributed greatly to Britain’s strategy of repositioning the City of London as a global hub for financial and legal services at a time of reduced international influence. While ownership of IPC was internationalised, the company was headquartered in London, and its chairperson was required to be British. The US and French partners were also considered to be domiciled in London for legal purposes, and thus subject to English law and English courts in the case of any dispute.

During the inter-war years, over production became an issue, as new fields - around the world as well as the Middle East - came on stream. The Great Depression of 1929 exasperated the situation. Until then, the IPC consortium had the power to control oil output and therefore the price. The RLA had consolidated this process:

A confidential French government memorandum noted in 1929 that the signing of the RLA ‘marked the beginning of a long-term plan for the world control and distribution of oil in the Near East’.

Following the signing of the RLA, the key players met secretly in Achnacarry, Scotland. Known as the Achnacarry Agreement, it would set the stage for future oil production globally (outside the US). It wasn’t just production of oil, infrastructure would be controlled depending on global demand. Ultimately it became the blueprint for what effectively became a cartel, with the price of oil raised artificially to match more expensive US crude. In short, it manifested itself as ‘organised plunder made possible by colonial rule.’

But another global shock was on the horizon. The first world war initiated a transition toward an oil dominated global economy. As the world once again became engulfed in conflict, oil was the lifeblood driving the war machine of World War 2. Following the war, the oil industry expanded rapaciously, as other industries opened up; agriculture, petrochemicals and many other uses for oil based products. By 1949, the ‘Seven Sisters’ controlled around 82% of crude reserves, 86% of crude production, 77% refining capacity, and 85% of cracking plants. They also controlled most of the global infrastructure. The US had become the driving force of oil production and supply. The US Government observed, that:

‘there are no other companies operating in international markets capable of supplying petroleum products’, and the ‘power of these [seven] major companies is so substantial as to be virtually unchallengeable’.

An important milestone after the war was the implementation of the Marshall Plan. This formed the basis of European reconstruction that would also increase the further transition towards oil dependency. This gave US companies a key share of the European market. To avoid price anomalies in the US market, the Middle East became the focal point for European supplies. In short, the Middle East became a goldmine. Oil there was cheap to produce, was close to European markets and would become a major producer for the rest of the world. This then set the scene for a future that would have a strong bearing on the post war geopolitics of the region. A watershed was of course the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. The build up to this is well documented. But there's a less familiar side to the story.

The Zionist Connection

As Britain’s imperialist mantle subsided during the post war era, the US would eventually take over as the prevailing imperialist power. It would also find itself drawn into the Palestine question. And a key component of this issue was US control of oil in the Middle East. The book, Dying to Forget: Oil, Power, Palestine, and the Foundations of U.S. Policy in the Middle East, details how US foreign policy dovetailed its oil interests with Israel, as well as the conundrums of reconciling the fate of the Palestinians with the creation of Israel. Another important element here was the exclusion of the Soviet Union, with the cold war developing at the time. Ironically at the time, the US did not entertain the imperialist positions of Britain and France. US foreign policy took a pragmatic approach. This was attractive to Middle Eastern states, that saw the US as outside the imperialist camp. Pivotal to this was the development of close relations with Saudi Arabia, which gave US oil interests access to a strategic and vast source of oil reserves, which continues to this day. Iran also became a focal point, particularly with the election of Mohammed Mossadegh in 1951, who took an anti-imperialist approach and attempted to nationalise the oil industry. He was deposed in a western backed coup two years later. This allowed US interests to consolidate their presence further in the Middle East.

As the partition of Palestine dawned, the Jewish Agency (which operates on behalf of the World Zionist Organization) played a major role in reassuring the US that a future Jewish state would benefit US interests in the region. With US oil companies becoming nervous as uncertainly abounded, the oil question would become a focal point in such discussions. A key player here was Max W. Ball, who was the director of the newly established US Oil and Gas Division (OGD). Its remit was to provide ‘advice and recommendations to other agencies of the Federal Government, to the States and to the petroleum industry, relating to petroleum policy.’ Ball was effectively [President] ‘Truman’s Petroleum Consultant.’ In January 1947, the hearings of the House of Representatives Special Subcommittee on Petroleum in Relation to the National Defense of the United States began. These hearings would play a pivotal role in determining US oil policy in the Middle East, as well as other regions in the world - particularly from a defence standpoint. Also playing an important advisory role at the hearings was James Terry Duce, vice president of the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (ARAMCO), who outlined the importance of oil in military planning and operations as well as detailing the resources available in the Middle East. The Zionists followed up the hearings with some purposeful lobbying on the importance of partition and how it would benefit the US in the region, especially in the light of Soviet expansion. This was summed up in a Memorandum by Jewish Agency Office (“Note on Palestine Policy. Problem of Implementation” (No. 162), in Political and Diplomatic Documents, December 1947–May 1948 (Jerusalem: State of Israel Archives, 1979), 273.):

The paramount character of the American oil interest in the Near East is undeniable, but it is a patent fact that the Arab States have a greater interest in yielding their oil to the United States than the United States has in exploiting it. The cow is more anxious to be milked than anybody to milk it. By breaking their contracts with American oil companies, the Arab States would incur such suicidal sacrifices that any such apprehension may be safely dismissed as groundless. Saudi Arabia derives the bulk of its revenues from oil royalties. Iraq would certainly be unable to balance her budget without them. Syria and Lebanon, both in acute financial straits, have scarcely any prospect of solvency except through the proceeds of pipeline concessions. No Arab country has any means of obtaining revenue from oil resources except through its existing or prospective contracts with the United States.

Eliahu Epstein was the director of the Jewish Agency for Palestine's Middle East Department. He played a pivotal role in the discussions with the US. Following Israel’s establishment, he became the country’s first Ambassador to the US. As the book notes:

To judge by Epstein’s report to the Jewish Agency executive, he had learned from his “informant” that the above contributions of the future Jewish state would raise its prestige in oil company circles and in the State Department. Max Ball, who can be assumed to have been the informant, had significant contacts in both spheres, but particularly among those with an interest in oil. His reassurance suggested a future role for the Jewish state that was sufficient to alter its perception as fundamentally inimical to U.S. interests in the Middle East.

In short, the oil companies anticipated that development projects could function as an effective means of containing opposition movements and movements for change across the oil producing states and, more generally, the Middle East. Ball envisioned the future Jewish state as playing a useful role in this context, for which he offered his assistance, suggesting “that soon after the establishment of a Jewish Provisional Government, an attempt be made to meet, at least informally, some of the top-ranking executives of ARAMCO and to frankly review with them the situation, as we did in our conversation.” The “informant” indicated that “he would be glad to be of any assistance to us in this matter.”

Another important consideration here was the fact that Saudi Arabia was prepared to distance itself from the Palestine question. The benefits of a burgeoning oil market superseded the regional politics. This helped to make partition more palatable to the US. The relationship between Ball and Epstein helped to smooth the road to partition with the US, and the relationship of the Jewish Agency, along with US oil policy.

Following the creation of Israel in May 1948, any fears of an impact of US support for Israel evaporated, as far as oil production was concerned. Indeed the trajectory following partition was one of expansion. At that time, oil production was dominated by the seven sisters:

In 1952 the International Petroleum Cartel reported that the cartel with its Seven Sisters “owned 65 percent of the world’s estimated crude-oil reserves…. Outside the United States, Mexico, and Russia, these seven companies, in 1949, controlled about 92 percent of the estimated crude reserve.” In addition, the same seven companies “accounted for more than one-half of the world’s crude production…about 99 percent of output in the Middle East, over 96 percent of the production in the Eastern Hemisphere, and almost 45 percent in the Western Hemisphere.” Refining was controlled by the same companies.

Of paramount importance to Israel in those early years was to find a source of oil that didn’t rely heavily on Arab produced oil. As a result, Israel turned to the Soviets and a western aligned Iran. This was prompted by an Arab imposed oil blockade in the wake of Israel’s war of independence, which had a considerable impact on Israel. This led the US to the realisation of the strategic importance of Israel in the region. As the book sums up:

after independence Israel emerged as an asset. Washington then moved to ensure Israel’s orientation was toward the United States and the West, a prerequisite to its integration into the U.S. regional strategy. This same process led U.S. officials to reduce their pressure on Israel to comply with the recommendations of UNGA Resolution 194, notably on the repatriation of the Palestinian refugees, the adjudication of boundaries, and the internationalization of Jerusalem. The decision to defer to Israel on these core issues signified Washington’s subordination of the Palestine Question, and its legitimation of Israel’s use of force in its policy toward the Palestinians to calculations of US interest.

This revised U.S. policy toward Israel and Palestine represented “the end” of one phase of U.S. policy—which had been marked by support for UNGA Resolution 194—and the “beginning” of another, whose consequences are with us today.

This is the background which underpins the post war trajectory of Israeli/US economic geopolitical policy in the region up to this day.

Corporate Colonialism

EcoResolution offers this explanation of corporate colonialism:

Corporate colonialism allows businesses built on extracting natural resources for profit to use their might as means to take over occupied or foreign land, exploiting economic weaknesses to influence governments therein - who are often all-too happy to trade land for foreign investment (even at the expense of local peoples’ livelihoods). The land sold to investors is typically stolen from Indigenous people without their prior knowledge or consent, and commonly leads to their removal.

This certainly applies to Palestine as it does elsewhere, and fits in with the oil and gas dynamic in the region. To bring the current situation into perspective, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) published the report, The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: The Unrealized Oil and Natural Gas Potential (2019).

The report firstly outlines legal elements pertaining to the Occupied Territories, pointing out that:

an occupier is not the sovereign of the territory, but a temporary administrator. It therefore is not given the right to deplete the territory of its resources and other property and assets. International law is clear that an occupant may only use such resources to meet the requirements of the local population. More specifically, an occupant may not exploit the resources and assets of the territory to benefit its own economy and particularly not for the furtherance of its war-related aims. The real objective underlying the stipulations of international law is to remove any economic incentive to war and any means that would allow an occupant to prolong its occupation once hostilities have ceased.

In this context, Israel is regarded as ‘a belligerent occupant,’ a status that the Supreme Court of Israel agrees with. With respect to natural resources (Scobbie, 2011, citing United States v. Alfried Krupp et al):

“If, as a result of war action, a belligerent occupies territory of the adversary, he does not, thereby, acquire the right to dispose of property in that territory, except according to the strict rules laid down in the [Hague] Regulations. The economy of the belligerently occupied territory is to be kept intact.”

Secondly, the report outlines how the Palestinian economy is weak, through a trade imbalance. Yet before 1967, Palestine had a relatively stable economy. As such:

Under prolonged occupation, the Occupied Palestinian Territory has become a land on the verge of economic and humanitarian collapse in the West Bank and deep humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza.

This generates a dependency on the occupying power, excluding any opportunity for self-development, which has an adverse effect on subsequent generations - despite the taxes and other contributions made by Palestinians into Israeli coffers. Economic losses since 1948 are estimated to exceed $300 billion. Add to that a potential loss of around $68 billion related to oil and natural gas. This brings in the issue of property rights. As the report notes:

The current allocations of shared common resources in the region are not the outcome of agreements, negotiations or equitable principles. Rather, they reflect the asymmetries of power in existence and the abilities of the strong to impose their will on the weak. Not only are there no clear property rights assigned to Palestinians, the process of assignment is not based on economic principles but on the outcome of an asymmetrical political process. Israel has laid claim to and potentially utilizes the common contested resources beyond those that it would be entitled to under any rational and equitable allocation system consistent with basic international law governing transboundary resources. There is a profound dichotomy between the balance of power governing current oil and natural gas allocations in the region and the balance of interests of the regional parties.

This is as applicable to the wider region as it is to Palestine. The resources in Eastern Mediterranean are shared, common resources, claimed by all parties in the region. But Israel’s aim is to exercise control over the region, with the assistance of US and western interests. The report cites a note of caution here:

The balance of interests should prevail over the balance of power, and a reasonable and fair allocation principle should be devised to address the current asymmetries and anomalies. In the interests of international peace and natural justice, nothing less can work.

It has been confirmed by experts that vast reservoirs of oil and gas lies below the Occupied Palestinian Territory. According to the United States Geological Survey, there’s around ‘1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and a mean of 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas in the Levant Basin Province (map below)’.

As noted above though, following the election of HAMAS and the subsequent operation cast lead by Israel, Gaza’s gas fields now belong to Israel, in contravention of international law. As the report concludes:

To date, the real and opportunity costs of the occupation exclusively in the area of oil and gas have run as high as hundreds of billions of dollars. The list and scope of losses caused by occupation is extensive. These costs need to be identified, studied, estimated and documented, to facilitate future negotiations for a just political settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and for forging a lasting peace in the Middle East.

The key issue here is how gas and oil reserves are recovered. Intrinsically the whole approach by Israel to its energy exploration and production, has been shambolic. Although it has always been speculated that a wider market for gas reserves would open up, this has not been fully realised yet. But with the geopolitical changes currently unfolding in the region, that could all change.

A focal point here is the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, with BP as its key stakeholder. BP is no stranger to the region, with its predecessor APOC having established a firm foundation. This analysis from the Transnational Institute outlines how BP is effectively fuelling genocide.

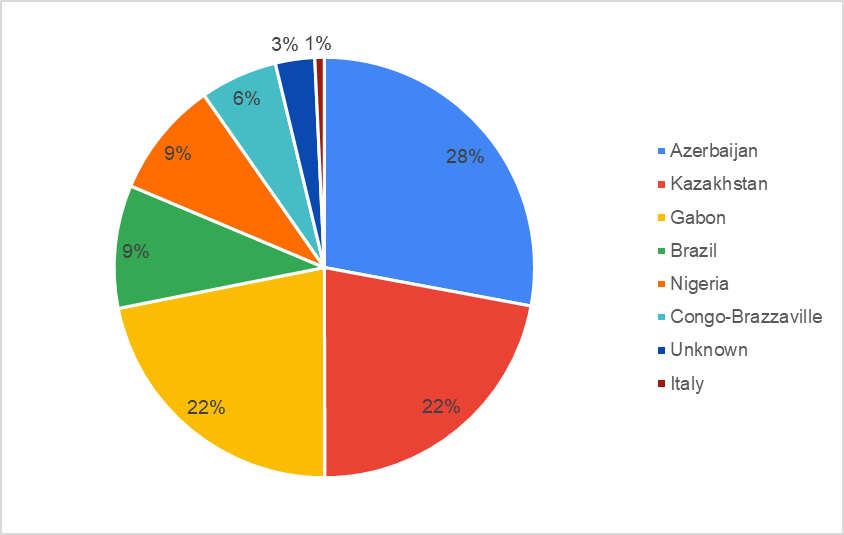

BP also operates the infrastructure of the pipeline, which runs from the Azeri–Chirag–Gunashli oil field in the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. It connects Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan and Ceyhan, a port on the south-eastern Mediterranean coast of Turkey, via Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. It currently supplies Israel with 28% of its oil.

The original oil company became BP in 1954. It was subsequently privatised after Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. Since then, the company has maintained a close relationship with the UK Government. The roots of the BTC can be traced back to collapse of the Soviet Union. BP was quick to recognise the potential in the newly independent Azerbaijan:

In 1992, Margaret Thatcher visited Azerbaijan upon the request of BP to cement ties between the burgeoning state and Britain. As former BP CEO John Browne recounts, “[it] was essential for us to be closely aligned with the UK government, as post-Soviet countries still found it easier to understand and accept government-to-government dealings.” Britain’s state endorsement of a project or potential deal was another negotiation tactic for BP to make the most of.

The US’s aggressive push for its presence to be felt in the Central Asian region also resulted in the creation of the US “Coordination Group on Caspian Energy” in 1998, which included governmental representatives and the CIA. This group met every three weeks to detail the short-term strategic plans required “to push both the oil companies and the governments of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey to build the pipeline that the US demanded.”

In 1994 a $7.4 billion “Contract of the Century” deal was inked. This would pave the way for western oil companies, along with BP to control production in the Caspian sea, with the BTC as the main transport artery. The final deal consolidated BPs control of the region for the foreseeable future. Given the prevailing uncertainty in Russian/western relations, this represents a vital strategic resource. From an Israeli perspective, once the BTC terminates at the Turkish coast, tankers transport the oil to Israel, arriving at the main port at Ashkelon, about 12 miles north of Gaza. As TNI notes:

The offshore trade route from Turkey is crucial for Israel’s oil supply and its disruption is an existential threat to the Zionist project. Due to Israel’s geopolitical isolation on land, it is entirely reliant on marine imports. The threat that the Zionist expansionist project represents to the sovereignty of neighbouring states means that there are no pipelines that directly deliver fuel supplies over land. This represents a serious geopolitical vulnerability and a weakness that countries like Yemen have tactfully exploited.

But it’s a two way street. Azerbaijan has become closely aligned with Israel, with Israel providing arms that have been linked to an offensive in Armenia, in 2023.

From Ashkelon, the oil is transported to the Ashdod refinery via the Ashkelon-Haifa pipeline, with jet fuel the main product, through a contract with the IDF.

By curious coincidence, this years (2024) UN climate summit (COP29) took place in Baku ‘at a time when the country’s oil and gas industry is on the cusp of further expansion.’ The COPs have become a front for backroom deals and wheeling and dealing.

Further context on BP’s and other companies role in providing oil to Israel is provided by Oil Change International in its report, Behind the Barrel: New Insights into the Countries and Companies Behind Israel’s Fuel Supply. Data for this report was produced by DataDesk. Next to Azerbaijan, Kazakstan supplies 22% of Israel’s oil, via the Caspian pipeline. The following infographic shows supplying countries.

The following table charts the oil companies involved in the supply of oil relative to each country (in kilotons).

Chevron is the second biggest supplier of oil to Israel after BP. In addition, the US has been supplying Israel with JP-8 jet fuel. How does all this stand under international law? This is outlined in a legal opinion published by Dr Irene Pietropaoli. As the report notes:

According to Dr. Irene Pietropaoli, Senior Fellow in Business and Human Rights at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, “Corporations and their managers, directors, and other leaders could be held directly liable for the commission of acts of genocide, as well as war crimes and crimes against humanity. Article VI of the Genocide Convention specifies that ‘persons’ may be held liable for genocidal acts – which include individual businessmen or corporate managers as natural persons and may include corporations as legal persons.”

Dr. Pietrapaoli also told us in an emailed statement that “Independently from home State regulation, companies that sell oil and fuel and other military supply to the government of Israel have their own responsibility to respect human rights and abide by international humanitarian law and international criminal law, as recognized in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ‘over and above compliance with national laws and regulations’. Corporations supplying jet fuel and oil to Israel may be providing material support to the military, aware of its foreseeable harmful effects, and therefore risk complicity in war crimes, genocide, and other crimes under international law.”

A matter of days after Israel began it’s assault on Gaza, BP was amongst the beneficiaries of a new round of licencing agreements awarded by Israel offshore. This video from Al Jazeera explores the background.

Chevron’s activities go beyond supplying Israel oil. It has a major stake in East Med gas fields (American Friends Service Committee), the Tamar and Leviathan, which are the largest fields. It is also linked to the East Mediterranean Gas (EMG) Pipeline, which runs from Israel to Egypt, off the shores of the Gaza Strip. As the AFSC piece notes:

Chevron made an estimated $1.5 billion in revenue from Tamar and Leviathan gas sales alone in 2022. Between 2021 and July 2023, Chevron spent over $21 million on lobbying the U.S. government, including on energy issues related to Israel.

In 2020, Chevron acquired Noble Energy, establishing its foothold in the gas fields. Israel’s tax revenue from the gas fields amount to the substantial sum of over $462 million. In short, Chevron effectively contributes to almost all of Israel’s gas fired electricity supply, controlled by the Israeli Electric Company. The impact on Gaza has been massive:

Chevron operates and partially owns the EMG pipeline, which connects Israel and Egypt, passing west of the Gaza shoreline. Regardless of its exact location, kept secret for security reasons, this pipeline is not under Israeli jurisdiction, and any economic gain in this area without Palestinian agreement is illegal under international law.

The Tamar processing rig and its pipelines are located about 13.5 nautical miles offshore near al-Majdal Asqalan/Ashkelon, just outside the territorial waters of Gaza. Over the years, the Israeli Navy has secured the rig, as well as the EMG pipeline, by restricting all shipping in the area—tightening the naval blockade on Gaza to 3–6 nautical miles—with devastating impacts on Gaza’s economy and fishing industry.

What’s currently happening in the region is the culmination of a plan that was formulated 30 years ago, surfacing after 9/11, as this video outlines.

Clark had seen a classified document from the Secretary of Defense's office saying that the US was going to take out seven countries in five years, starting with Iraq, and then Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and, finishing off, Iran. This was perfectly in keeping with the historical pattern noted in this article regarding resource consolidation. This was effectively confirmed by Clark in the video, saying that oil was the decisive factor. If there was no oil in the Middle East it would be just like Africa. Greater Israel may have been initially a Zionist dream. But for US imperialism, its a wet dream of oil and gas riches. 5 years prior to this, as noted by Jonathon Cook, a document called A Clean Break was produced:

It was all about securing Israel’s place as a forward base for US interests in the oil-rich region.

It proposed that Israel should tear up the Oslo Accords and any moves towards peacemaking with the Palestinians – the title’s “clean break” – and instead go on the offensive against its regional foes, with US backing.

The dominoes are tumbling. Syria has fallen. Lebanon has been weakened. The oil and gas claims of these two countries will likely be exploited by the west. It’s only a matter of time before Iran falls into the cross-hairs of the US empire. One final dimension to this geopolitical game that Cook touches upon is Russia’s preoccupation in Ukraine, which is probably by design. This has diverted its attention from the Middle East, opening the door for Israel to further its aims. The end game remains elusive, but perhaps predictable. The Ukraine/Palestine front has put Pandora’s Box back onto the agenda.

Update

At the time of publication, SOMO had just released a report Powering injustice: Exploring the legal consequences for states and corporations involved in supplying energy to Israel. It outlines the latest research and data pertaining to Israel’s supplies of energy.