The Environmental Consequences of the Occupation

The impacts of conflict and climate change will most likely leave Palestine/Israel uninhabitable.

Resources are a key factor in any conflict and inevitably environmentally related factors will emerge. This is as true for occupied Palestine as it is for anywhere else. Here, a path of systematic environmental degradation and resource prioritisation through the expansion of Israeli settlements has taken its toll, amongst other things.

Environmental Nakba

In 2012, Friends of the Earth International (FoEI) sent an observer mission to the West Bank to witness the environmental impacts of the Israeli occupation. The Report Environmental Nakba Environmental injustice and violations of the Israeli occupation of Palestine (Nakba: Catastrophe in Arabic) outlines the findings of the mission.

Expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank appropriates land from the Palestinians, an important agricultural resource. Settlers are given access to water in contrast to the Palestinians where water is restricted. This stems from an Ottoman period law which:

permits the state to expropriate land which is not in use – evidence for which is ensured by military exclusion, vandalism and intimidation by settlers, and fabrication.

Palestinians have access to around 10% of available water, whereas settlers have access to 90%, using 300 litres per person per day, compared to the Palestinians’ 15 litres, which is often transported by donkeys and carried on women’s and children’s heads over long distances.

Available water in the West Bank comes from three connected mountain aquifers; the Eastern, Western & North Eastern, controlled by Israel, and water from wells, springs and rainwater harvesting, with the remainder coming from the Israeli state water company Mekarot. Water restrictions have been in place since 1967. This includes access to the Jordan river, with the adjacent land declared a closed military zone. Due to heavy abstraction by Israel, the river has dried up downstream. This has generated its own environmental problems.

Another major source of water disruption has been the construction of the segregation wall. Its route has cut off access to many of the wells that Palestinians have depended upon for centuries.

The geography and background behind these problems is linked to the Oslo Accords. Oslo 2 divided the West Bank into three administrative divisions; Areas A, B and C. The distinct areas were given a different status, according to the level of self-government Palestinians would have, through the Palestinian Authority (implemented as part of the Accord), until a final status accord could be established.

The Areas are not contiguous, but rather fragmented depending on the ethnicity of the population in the areas, as well as the areas Israel has reserved for itself on the basis of what it perceives to be military requirements. The maps below show the extent of the respective areas.

Area A is under full civil and security control by the Palestinian Authority; circa 3% of the West Bank, which includes East Jerusalem. Area B comprises Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control; circa 23–25%. And Area C is subjected to full Israeli civil and security control; circa 72–74% of the West Bank.

A tactic used by settlers is the widespread disposal of waste water and sewerage onto Palestinian land and watercourses. In addition industrial waste is also routinely dumped, with little or no controls, ultimately impacting the health of Palestinians living near industrial zones.

From a biodiversity perspective, the West Bank is recognised a unique habitat by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN):

The area is regarded as an Important Plant Area by the IUCN and “is a reservoir of medicinal plants for Salfit and Nablus cities and contains many species protected by law such as Ophrys species and Tulipa agenesis.”

Palestinian land owners worked in harmony with nature, until the occupation, with olive plantations a major industry. This has been heavily disrupted by Israel, with thousands of olive trees uprooted and destroyed. Israel has also used greenwashing to acquire ‘green space’, a euphemism for ethnic cleansing, with the Jewish National Fund (JNF) a major benefactor here.

The FoEI mission followed in the footsteps of an investigation by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: occupied Palestinian territory (OCHA). Its key focus was the encroachment of springs — a vital commodity for the Palestinians — by Israeli settlers in the West Bank. These springs flow naturally to the surface from groundwater and have provided a source of water for centuries, providing water for irrigation in the West Bank, meeting domestic and livelihood needs, and serving as sites for leisure and family recreation. This has become increasingly restricted by Israeli settlers, through threats and intimidation. Some of the well documented incidents include:

shootings, beatings, verbal abuse and threats, stone throwing, unleashing of attack dogs, striking with rifle butts and clubs, destruction of farm equipment and crops, theft of crops, and killing or theft of livestock, among others. Between 2006 and 2011, OCHA recorded over 1,300 settler attacks throughout the West Bank resulting in either casualties or property damage.

In most cases there was collusion with the Israel Occupation Forces (IOF). Settlers have also fenced off areas preventing access to Palestinians. This is illegal under International and Israeli law. But the authorities are turning a blind eye to these activities:

The root of the settler violence phenomenon is Israel’s decades-long policy of illegally facilitating the settling of its citizens inside the occupied Palestinian territory. This activity has resulted in the progressive takeover of Palestinian land, resources and transportation routes and has created two separate systems of rights and privileges, favoring Israeli citizens at the expense of over 2.5 million Palestinians.

Many of these areas are converted into tourist attractions, archaeological sites and various other cultural and artistic events, usually promoted and funded by the Israeli government through the Ministry of Tourism, the Nature and Parks Authority, as well as the JNF. This has effectively normalised settlements since 1967.

The report points out:

Under international law settlements violate Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the transfer of the occupying power’s civilian population into occupied territory. This illegality has been confirmed by the International Court of Justice, the High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention and the United Nations Security Council. Settlement policies and practices have also resulted in the infringement of a range of provisions in international human rights law, including those enshrining the right to property, to adequate housing, to freedom of movement, and to be free from discrimination, among others.

Following the Oslo accords, an Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee (JWC) was established to regulate the use of water resources. But it was a one sided arrangement that allowed Israel to veto or delay water-related projects in Areas A and B and in much of Area C. This has stymied various water projects submitted by the PA. Palestinians have also been denied access to water from the Jordan River, the main surface water resource in the West Bank. As a result, they became dependent on the Mountain Aquifer, which is a transboundary water resource. Under international law, this is to be shared by Israelis and Palestinians. But, ‘it is estimated that Israel uses over 86 percent of the water extracted from the aquifer, compared to less than 14 percent by Palestinians’. This pattern of use could lead to water shortages for Israeli’s as well as Palestinians.

Wasting away

The FoEI report highlights the issue of waste and pollution, and lack of oversight by the Israeli authorities concerning this. Liquid Waste — sewage and industrial —is dumped onto Palestinian water-courses and agricultural land, rendering it contaminated and unworkable, making it easier to confiscate under the ‘unused land’ rule, much of it coming from settlements. Israeli restrictions prohibits any Palestinian community from developing their own wastewater treatment system without treating the wastewater of the nearby settlements. Therefore, treatment of wastewater from Palestinian communities in the West Bank is inadequate, with more than 90% of wastewater from Palestinian homes untreated and either collected in cesspits or discharged onto wadis. Toxic dumps of industrial and chemical waste has led to water contamination:

tests have revealed water contamination with lead and “revealed the presence of 17 poisonous chemicals, some of which are internationally forbidden”. Levels of cancer and gynaecological irregularities are reportedly exceptionally high in the local villages of Jayyous and Azzun.

There’s also documentation of hazardous waste being smuggled into the West Bank from Israel for illegal dumping, with military forces dumping highly toxic and nuclear waste in the occupied territories. Industrial complexes within the West Bank are allowed to pollute with impunity, and that:

Even the Israeli State Comptroller described these conditions as “bordering on lawlessness” which “place the well-being, health and lives of the workers in the industrial zones in real danger”.

B’Tselem investigates the waste issue in detail in their report Foul Play: Neglect of Wastewater Treatment in the West Bank (2009). The general consensus of the report is that waste water treatment in the West Bank is inadequate and ineffective.

Waste water from settlements have polluted water courses, where in many cases, waste treatment facilities have been inadequate. Waste has also flowed into the mountain aquifer:

in an area sensitive to pollution. The raw wastewater creates a horrible stench and serious sanitation and environmental hazards, including pollution of groundwater and of the Dead Sea. Also, some of it serves as drinking water for sheep and goats and is used for irrigation of Palestinian farmland, despite the health risk. For these reasons, the Ministry of Environmental Protection has defined this wastewater flow as “the greatest wastewater nuisance in Israel.”

Waste from Palestinian areas are also poorly treated. This is partly ‘due to Palestinian refusal to cooperate in projects that may legitimize settlements.’ This position was adopted by the PA following its establishment. Another problem is the bureaucracy surrounding proposals to establish wastewater treatment and the lack of cooperation of the relevant authorities. These are the Joint Water Committee (JWC), which is an Israeli-Palestinian committee, who’s remit includes the approval of new water and wastewater projects in the West Bank, and the Israeli Civil Administration, the Israeli governing body that operates in the West Bank, set up by Israel in 1981. As soon as wastewater flows into Israel, its a different story. The waste is treated there with a substantial proportion of the cost loaded onto the PA. Ultimately, the lack of any meaningful solution to the problem delays:

implementation of a proper solution for treating Palestinian wastewater and ignore the flow of Palestinian wastewater in the valleys of the West Bank and seepage of pollutants into the Mountain Aquifer, as the wastewater makes its way to the facilities in Israel.

The inevitable consequences of the generation so much pollution is contamination of the land, directly affecting food production. This can create long term problems of reduced land fertility, leaving swathes of land unusable. It also has broad biodiversity impacts, with many local species of flora and fauna becoming extinct as a result. The issue of wastewater and pollution in the West Bank constitutes yet further breaches of International law by Israel, which is par of the course. Israel treats international law with arrogant contempt:

Article 56 of the Fourth Geneva Convention imposes on the occupying state the duty of “ensuring and maintaining, with the cooperation of national and local authorities… public health and hygiene in the occupied territory.” This article imposes on the occupying state primary responsibility for ensuring public health and hygiene in order to prevent the spread of disease and epidemics.

The obligation to protect water sources is also derived from the occupying state’s duty to ensure “public order and safety.” This duty includes not only the negative obligation to refrain from harming the local population, for example, by damaging water sources and their supply, but also the positive obligation to take suitable means to protect the population from dangers to which it is exposed.

The Israeli High Court of Justice largely agreed with this, whereby every person has a right to an “adequate standard of living” and to “the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health,” as defined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

The key issue here is that the environmental problems developing in the occupied territories could impact in Israel in the future:

Studies conducted by the Nature and Parks Authority warn that, “sooner or later, critical damage will be caused to Israeli and Palestinian water sources.” The Palestinian Applied Research Institute Jerusalem has stated that the neglect constitutes “a grave environmental threat,” and a delegation of the UN Environmental Program declared that “urgent action” was necessary to address the neglect.

Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink

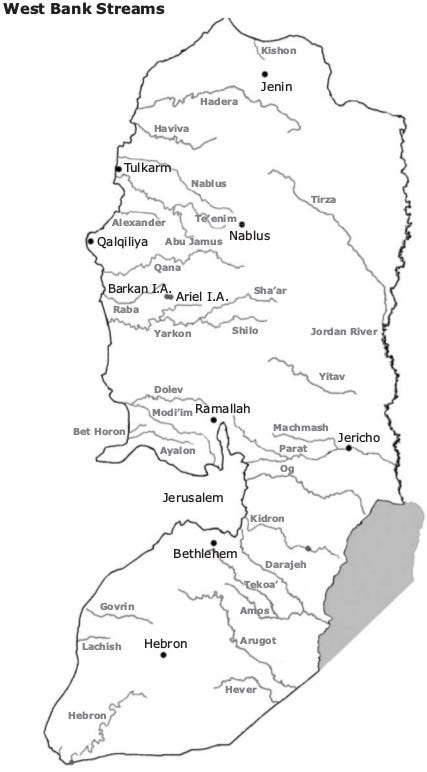

Streams are a vital lifeline for Palestinians in the West Bank (map below).

The aquifers also provide a vital source of groundwater. In The Human Right to Water in Palestine (2012), a report commissioned by the Blue Planet Project, the issues of water availability are further explored. Gaza has relied on the Coastal Aquifer for freshwater, but this has been highly depleted and polluted with high levels of salinity, rendering it undrinkable. Many access wells in Gaza have been damaged or destroyed by Israel.

The West Bank relies on the Mountain Aquifer. The Western Aquifer is the most abundant, recharged on a constant basis by good rainfall. But Israel has restricted Palestinian development of this resource.

Israel also fully controls the Jordan River, which has been diverted to Israel’s coastal plain and the Negev desert, with major impacts on the riparian ecosystem, peace in the region and access to water for many Palestinians and Jordanians. As a result, Palestinians have become largely dependent on Mekorot.

Of great contention is the so called apartheid wall, which effectively separates Israel from the West Bank. The wall has intentionally tracked a route that would give the Israelis almost exclusive access to the western aquifer, impacting Palestinian access to water. Built in 2002, it’s twice the size of the Berlin Wall at some points. The route of the Wall generally tracks the internationally recognized 1949 Armistice Demarcation Line, or Green Line, between Israel and occupied Palestinian territory:

The Wall grabs Palestinian wells, springs and cisterns that Palestinians have depended on for centuries. The Wall is also designed to capture most of the few future potential Palestinian abstraction zones of the Western Aquifer.

Israel’s deep productive wells tap into the Western Aquifer almost exclusively from within Israeli territory, compared to less than a handful of Israeli wells accessing the Western Aquifer from inside Palestinian territory. If the Wall becomes the new internationally recognized border between Israel and Palestine, then Israel will have pre-empted negotiations over an increase in Palestinian shares and abstractions in this shared basin. Israel will retain near-exclusive control of this basin and its benefits, even though it is recharged largely inside the West Bank. Thus it would be able to prevent Palestinians from accessing significant reserves in the Western Aquifer even after the formal military occupation is over.

The Alliance for Water Justice in Palestine focuses on the issue of water. Formerly the Boston Alliance for Water Justice, based in Massachusetts, its remit is to:

raise awareness about Israel's use of water as a weapon against the people of Palestine.

Citing core principles That:

Water is a human right

Water should not be privatized

Water should not be used as an instrument of oppression

Water should be equally distributed

The organisation is fully aligned with the BDS campaign. A series of briefings (below) outlines the current state of affairs within the Palestinian Occupied Territories.

Even before the current genocidal attacks on Gaza, the situation there was dire. In 2012 the UN predicted ‘that the Gaza Strip would be unlivable by 2020’, and that the coastal aquifer ‘will suffer “irreversible damage” unless urgent steps are taken to address the water crisis.’ In 2014 much of the Gazan infrastructure was damaged. Coupled with electricity shortages, water pumps didn’t work ‘causing large sewage lakes to form.’ On one occasion a ‘lake overflowed, drowning 5 people in a nearby village.’ It’s also noted that:

The World Heath Organization estimates that water contamination is responsible for 26% of all disease in the Gaza Strip and that half of the children suffer from water-related parasitic infections, and many babies suffer from “blue baby syndrome” due to the excessive nitrates in the water.

Illegal settlements have had a major impact on water infrastructure in the West Bank. During the summer, Israel diverts about 50% of the water supply to accommodate settlers’ needs. Those ‘needs’ can include swimming pools, spas, farms, and orchards. In particular:

No Israeli settlement in the West Bank has a sewerage system. Their wastewater and sewage is released into Palestinian water sources and land. 80% of the garbage generated by Israeli settlements is dumped on Palestinian land. Nearly half of Palestinian children in rural areas now suffer from diarrhea (the biggest killer of children under 5 years old in the world) because of sewage and poor water quality.

The Alliance clearly notes the violations in international law:

The right to water and sanitation, and the right for a people to make use of their natural wealth are human rights under international law. The Fourth Geneva Convention, signed by Israel, prohibits an occupying state from discriminating between residents of occupied territory, BUT Israeli colonists in the West Bank are allocated much more water than Palestinians.

This infographic sums it up:

How water rights are actually applied can be complex. There are various areas under international law that apply to this. This report covers the issue in more detail.

Dead Sea Degradation

The Dead Sea region is extremely vulnerable. It is an area of high ecological importance. EcoPeace Middle East has conducted extensive research, outlining the background to the problems in the region, noted for its unique geographical, biological, and historical characteristics. It is the lowest point on earth and world’s saltiest large water body. The Dead Sea is disappearing due to steady evaporation and lack of replenishment from the Jordan River and side wadis (tributaries). The construction of dams, reservoirs, and pipelines has taken its toll in the basin, with much of the water used for highly subsidised and inefficient agriculture. Over the past 50 years, the Dead Sea has declined by 30 metres. In addition, mineral industries have sprung up in the area, who’s harvesting of minerals are having considerable environmental impacts. This is due to the construction of evaporation pools in the southern basin of the Dead sea since the late 1960s, where the minerals are harvested. This has directly caused 45% of the sea level retreat, with a 4% increase in salinisation. Unless there is tight regulation of the industry, the impacts will continue.

With extended drought conditions forecasted in the region as a result of climate change, the threat of extreme water scarcity is very real. Releasing water sourced from treated wastewater and desalination plants into the area could improve the situation. However, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) would be required.

Another major impact was the appearance of sink holes predominantly along the western shores of the Dead Sea. This photo-map shows the extent of the problem. As a result, settlements and tourism have been eradicated in the area.

This detailed video gives an excellent background to what’s going on around the area.

One major proposal was to build a link to the Red Sea, called the Red Dead Canal Project. The aim was to transport water from the Red Sea in the Gulf of Aqaba, through a series of canals and tunnels up over the coastal ridge and down to the Dead Sea. The conveyance would be utilised to generate hydroelectricity and desalinate water, with drinking water to be pumped to regional population centres and desalination brine discharged into the Dead Sea. However in 2021, Jordan shelved the plan that had surfaced in 2005. In 2013, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian Authority had decided to go ahead with the project. But according to Jordanian King Abdullah, there was “no real Israeli desire” to push ahead with the plan. Given the current tensions in the Middle East over Gaza, it seems unlikely the plan will reach fruition any time soon.

Climate Change

The paper, Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (2022), published in the Journal Reviews of Geophysics, by the AGU, outlines how the region is a climate hotspot. Records from the beginning of the 20th century have shown that temperatures in the EMME have increased about 2 times faster than the global average. As shown in the screenshot below, temperatures have warmed in the EMME by around 0.45C/decade since 1981 compared to 0.41C/decade for Europe. The global average was 0.27°C/decade.

Over the past 10 years, dramatic temperature peaks have been recorded:

The Kuwaiti city of Nawasib recorded 53.2°C, the highest temperature in the inhabited world in 2021.

And:

In the arid regions of the Arabian Peninsula and east Iran, summer land surface temperature, usually derived by satellite sensors, routinely soared above 60°C. In 2018, the world highest land surface temperature of 80.8°C was observed in the Lut Desert in Iran. The Arabian or Persian Gulf recently also recently experienced record-breaking sea surface temperatures. On 30 July 2020, sea surface temperatures in Kuwait Bay reached 37.6°C.

Future projections forecast much of the same, but with with greater intensity and frequency, especially during the summer. As the paper notes, ‘extreme heatwave characteristics in the region are projected to increase tremendously.’ Indeed temperatures could get as high as 60°C. Then there is urban heat island (UHI) effect, which exasperates temperatures in urban areas. These conditions will cause critical heat stress, with ‘widespread adverse impacts on public health, the water-energy-food nexus and other socio-economic sectors’. In short:

Calculations of the heat index (combined effect of high temperature and humidity) corroborate that several areas across the region may reach temperature levels critical for human survivability.

The eastern Mediterranean and Gulf regions are likely to see increased sea surface temperature, which could have impacts on wind and dust storm incidents. More broadly, prevailing wind and weather systems are likely to move further north generating drier conditions. Also what the paper describes as high-impact extreme precipitation events, that may lead to flash flood scenarios, are projected to occur. Palestine/Israel and the surrounding area are most likely to suffer increased drought conditions. The paper notes:

The Fertile Crescent is expected to dry, and its fertility will be challenged by the end of the century (Kitoh et al., 2008), with significant drying of the Euphrates and Jordan rivers (streamflow decreases of 29%–73% and 82%–98%, respectively). The Euphrates discharge regime has changed substantially since the construction of the first dams in the 1970s, while the natural flow may be expected to drop by ∼70% in high-warming scenarios.

In keeping with global trends, there will be a lengthening of the summer season with shorter winters. Heat increases will be accompanied with increased humidity, particularly near coastal regions. Arid zones will expand, with increasing desertification and wind erosion.

Another important element is sea level rise. The current measured rate is about 3.1mm/year globally. This projects to a 1m rise towards the end of the century, caused by a combination of thermal expansion, and significant land-ice mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica. Indeed as the paper notes:

Indications of Antarctic land ice destabilization are steadily gaining support, strengthening the likelihood of the significant acceleration of sea-level rise (SLR) during the present and following centuries. This will potentially affect coastal settlements, infrastructure, agriculture and cultural heritage sites.

The projected adverse conditions will impact agriculture with rising temperatures affecting the production of familiar crops in the region such as olives. These factors along with increased energy demands will increase tensions in an area fraught with security issues. This could lead to widespread migration - so-called climate refugees. Indeed:

The scale and geographic scope of such population displacements could be one of the greatest human rights challenges of our time.

And:

The additional stress from climate change to prevailing conflicts between countries and populations may have dire consequences for weakened populations, also in refugee camps, exposing them to high risks and contributing to migration, with the associated suffering from malnutrition, poor sanitation and a lack of medical and mental support infrastructure.

I’ve previously covered the relationship between conflict and climate change.

As I noted this was an area of concern that:

is a source of considerable direct destruction and a significant emitter of greenhouse gases. It is also one of the biggest financial black holes on the planet. If some of the money spent on conflict over the past few decades had been spent on sustainable development instead, we probably wouldn’t be facing a climate crisis.

The focal point here was the role of the US military machine, which outspends other countries and is directly facilitating Israel’s genocide. It also goes without saying that Israel itself has been spewing out carbon during its onslaught in Gaza. How then can climate change and conflict be reconciled? This has led to the the emergence of the concept of environmental peacebuilding (EP). A key player here is the Environmental Peacebuilding Association, initially established in 2018. It notes that:

Environmental peacebuilding integrates natural resource management in conflict prevention, mitigation, resolution, and recovery to build resilience in communities affected by conflict.

This paper, Environmental Peacebuilding: Moving beyond resolving Violence-Ridden conflicts to sustaining peace (2024), published in the Journal, World Development, focuses on the relationship between Israel and the UAE, two countries that don’t share a common border and have never been in conflict. Although to some extent the paper ignores the elephant in the room, namely the international isolation of Israel, it nevertheless makes an important observation in using EP as a means of breaching the conflict/climate nexus. If climate change is the greater problem, that relationship needs to be identified.

The paper does point out some positive outcomes between the two countries in terms of the development of green technology. However it also notes that much of the cooperation between the two countries are symbolic, and the recent actions by Israel related to Gaza has put a strain on the relationship, with the UAE openly criticising the current regime in Tel-Aviv, with similar reactions from other countries in the region who have also played a role in EP and green tech cooperation. The paper notes in this respect:

For a more profound and enduring cooperation to take root, it is essential to address the underlying Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the absence of a resolution, collaborations are likely to remain surface-level, restricted largely to ventures that offer immediate economic gains.

This is a crucial point, not just within the context of the Palestinians, but to other marginalised communities around the world. It’s well documented that climate change will have a greatest impact on the most vulnerable.

To further elaborate on the concept of EP, UNEP has developed an Environmental Cooperation and Peacebuilding programme, covered in itsEvaluation of the Environmental Cooperation for Peacebuilding Programme report (2016).

The programme was launched in 2008, its stated objective:

to strengthen the capacity of fragile States, regional organisations, UN entities and civil society, to assess and understand the conflict risks and peacebuilding opportunities presented by natural resources and environment in order to formulate more effective response policies and programmes across the spectrum of peace and security operations.

Curiously the report reveals that:

the ECP programme was never externally communicated and marketed as a discrete programme itself. As a result, few individuals are knowledgeable about the full scope of the ECP programme – and most only have experience with the programme at the intervention level.

rather the individual thematic reports and products of ECP, are the focus of marketing and advocacy. The role of the initiative is to catalyse other initiatives, and this defines the operational structure.

A paper published in the journal, Sustainability Science, Ownership and inequalities: exploring UNEP’s Environmental Cooperation for Peacebuilding Program (2021) though, is highly critical of the UNEP approach. Over and above the technical qualitative analysis undertaken, the general findings are that UNEP tends to focus more on international state actors on EP polices, with a distinct absence of international non-state actors. Another important point is the reduced role of domestic actors. Local knowledge and understanding of various issues can be brought into context more readily by domestic actors. International non-state actors would generally be represented by NGOs, who may have an important input in relation to domestic issues and their relationship with domestic actors. The paper notes:

In light of this, important questions arise not only regarding UNEP’s environmental peacebuilding practice but wider UN action around natural resource management in conflict-affected settings. Specifically, the use of these reports as training material for UNEP and other UN staff may discourage practitioners from involving domestic state and non-state actors, and as such potentially inhibits sustainable management of resources, as well as impacting wider peacebuilding efforts.

Another important point noted by the paper is:

that environmental peacebuilding approaches tend to overemphasize technical solutions and so depoliticize the issues faced, thereby ignoring the highly political reality, especially in local contexts.

With respect to Palestine, there is little doubt that the occupying power has no interest in EP - or any other type of peacekeeping. But many other actors are. Since October 7, 2023, we’ve seen anti-war and environmental protesters coming together under a common cause. There may be scope for expanding the EP concept more widely. But perhaps there’s a key message here. The UN has come under criticism due to its vulnerability to political interference from powerful states such as the US. Everything is driven by the free market through a neoliberal economic system. The technology aspect is very much a part of that. And Israel is a case in point, a country driven by power and high tech superiority, reflected in both its military prowess and its response to the climate crisis, with its ‘battle tested’ weapons systems. We see this also reflected in the response to an imagined threat from Iran with the deployment of the Stuxnet worm, discussed in the previous article in this series. And as outlined below, Israel has approached the water shortage problem by building desalination plants. However as with many touted solutions to environmental problems, there are trade off’s.

Desalination, saviour or false solution?

A study, The state of desalination and brine production: A global outlook (2018), published in the Journal, Science of the Total Environment, outlines the methods of production.

Desalination is the process of removing salts from water to produce water fit for human consumption and other uses. It’s an expensive process, but improving technologies could reduce costs. However environmental oversight could impact the process also, due to the production of brine, the waste effluent left over after the usable water is produced. There are two main types of desalination production; Thermal - using fossil fuels, which tends to dominate the MENA region; Reverse osmosis (RO), which is becoming the most prominent method of production, is a process to purify or desalinate contaminated water by forcing water through a membrane. Thermal tends to be less efficient than RO, although it also depends on the salinity of the water. The higher the salinity the more difficult the process, the more expensive also. When it comes to sea water, the two processes are fairly comparable.

Brine production is high in the MENA region, and as the paper notes:

With increasing water demands coupled with water scarcity intensification, desalination is expected to expand rapidly in the future. The expected expansion in desalination capacity will be commensurate with an increase in the volume of brine produced. Management of the reject brine is the still a major problem of desalination, containing both elevated salinity (relative to feedwater type) and chemicals used during pre- and post-treatment phases in the desalination operation.

As such:

The high economic costs and energy demands of brine treatment and mineral recovery methods remain a significant barrier to more widespread application.

The paper Climate change and security in the Israeli-Palestinian context (2012), focuses on desalination in Israel. It notes the continuing extensive desalination program going on in Israel (map below). Ideally from the Palestinian perspective, desalination can be used by Israel as a means of producing fresh water, whilst Palestinians can utilise ground water and be given greater control. Desalination may have been a solution to the water problem in Gaza, but given recent events, the days of a Palestinian presence there may be numbered.

Ultimately the only solution to dealing with climate related stress in the region is cooperation. But as the paper notes:

the growing mistrust between the parties and the securitization of perceptions, manifest in the framing of discussions of cooperation within a power perspective, have discredited cooperative proposals, mainly by the Palestinians. Thus, the prospects for cooperation on climate change, when they are set within a security and power nexus, are arguably lower, thereby impeding the coordination of adaptation strategies.

Another paper, Desalination, space and power: The ramifications of Israel’s changing water geography (2011), in the Journal, Geoforum looks at the wider issues.

Historically, water in Palestine was available from local cisterns, wells and springs. Since the 1930s, the Zionists began constructing water carrying infrastructure along with some British Mandate systems. It was during this pre-war period that the Mekorot water company was formed. Following the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948, large scale systems were built. This led to the creation of the National Water Carrier (NWC) in 1964, ‘forming a national system that conveyed water from the relatively water-rich north, southward.’ Geographically there were three main storage basins, Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), the Coastal aquifer and the western mountain aquifer - all eventually connected via the NWC and under the control of Mekorot (map below). But this generated a side-effect. The Jordan river dried up. This was compounded by increasing use from Jordan and greater agricultural and domestic demands in Israel. Following the 1967 occupation, greater restrictions were imposed on Palestinians. The result of this increased demand was greater abstraction from the three aquifer basins.

In the late 1980s, disaster struck. A period of drought hit the region, culminating in the extreme drought of 1998–2001. This was the trigger that forced the Israeli government to approve its large scale desalination program, with the aim of providing about half of water required by Israel. Plants are located mainly along the Mediterranean coast. Whether desalination can be a substitute for natural fresh water is debatable. The chemistry of desalinated water is slightly different. There’s another side to the debate, as a commercial issue. Israel - like its western allies - has embraced the neoliberal agenda. The paper notes:

As desalination opens the way for the introduction of new capital along the sea shore, it potentially undermines entrenched interests and institutions whose power stems from the existing water geography. Thus, desalination may serve to undermine the power of existing river basin authorities or similar bodies whose power is based on their ability to control water flows downstream through dams. Desalination can serve thus as a mean for overcoming the spatialities that hindered the neoliberalization of water.

Indeed an interesting player has emerged that warrants further investigation. This is IDE (covered later). The following table outlines the major players in the desalination field.

Some important issues have been raised above. Firstly the severe drought. According to a NASA study the 1998–2001 drought was the worst of the past 900 years. This is in keeping with climate predictions whereby low frequency high impact events will become the new norm.

Secondly, within the context of EP, the Environmental Peacebuilding paper highlights the role of the Middle East Desalination Research Center (MEDRC). It emerged from the Working Group on Water Resources, set up following the Madrid peace conference in 1991. Based in Oman, MEDRC states on its website that it:

was established to address two of the greatest global grand challenges – peace and environmental sustainability. Established as part of the Middle East Peace Process, MEDRC is a unique International Organization that works to build solutions to freshwater scarcity across borders and divisions.

Its current focus is desalination research. However as the paper notes, its influence has been limited, ‘often labelled as a ’talking shop’ with member states exhibiting lacklustre engagement,’ those states being ‘Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Jordan, Qatar, and Oman, with the U.S. being instrumental in its facilitation and funding.’ However MEDRC may have a role to play in future regional dynamics.

Thirdly, to elaborate further on the brine effluent issue, this paper, Environmental impacts of desalination and brine treatment - Challenges and mitigation measures (2020), published in the Journal, Marine Pollution Bulletin, reviews the available evidence.

Given that desalinated water can be used for different purposes, which can determine the process and purity of the water produced, the paper notes ‘there is no worldwide regulation on the freshwater purity for human consumption,’ although there are recommendations. Thermal plants use fossil fuels, but RO plants require electricity to operate, most likely produced by fossil fuels. Increasingly technologies are emerging that can process brine.

Life cycle analysis is a way of understanding the wider impacts of a given process. The paper makes this vital observation:

The vast majority of industrial processes have both positive and negative impacts on the natural environment and society. Therefore, if there is an alteration to the natural environment, either by a human or by nature, we experience an impact on the environment. The same behavior is observed at desalination. Desalination process involves different activities, some of which take place only during plant construction (e.g., construction of electricity and sewerage networks), while others are present during plant lifetime (e.g., pretreatment and post-treatment). In particular, activities such as clearance and grading of the project area, connection to electricity and sewage networks, construction of facilities and access roads, feed water intake, by-product discharge, storage and transport of desalinated freshwater, use of pretreatment and post-treatment chemicals, noise and vibration, etc. change the natural state of the environment and may have an adverse impact. Given that desalination plant lifetime ranges from 20 years to 35 years, it is easy to understand that environmental aspects are equally important as the commercial aspects and should therefore be considered.

The process uses various chemicals at different stages of production such as; antiscalants (polyphosphates, phosphonates and polycarbonic acids), flocculants (cationic polymers) and coagulants (FeCl3, Fe2(SO4)3), some of which may be present in the effluent. The following table lists disposal methods.

Coastal brine discharges can impact marine ecosystems:

In particular, the most significant impact that may occur on marine species such as fishes, plankton, algae, seagrass, etc. is the ‘lethal osmotic shock’ due to irreversible dehydration of their cells. As a consequence of dehydration, there is a reduction in turgor pressure that could result in the long-term extinction of the marine species.

These impacts are more pronounced in closed, semi-closed and shallow areas where there is reduced circulation, such as the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. It is therefore important that EIAs are conducted and appropriate Environmental monitoring plans (EMPs) are developed to monitor the situation.

A major review report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Israel 2023, notes:

Israel’s environmental regulatory framework is fragmented. Some environmental laws (on biodiversity protection, water and waste) have been in place for decades. Regulatory uncertainty is a significant challenge for businesses. The uncertainty is caused by frequent government changes and resulting policy fluctuations, as well as the inability of recent caretaker governments to pass legislation.

Since Israel joined the OECD in 2010, there has been little progress in the EIA process. It is fragmented, outdated and less developed than in the EU. Regarding desalination, the report notes:

desalination has adverse environmental impacts. Apart from being highly energy intensive, the process produces brine. Discharges of brine into the sea can lead to increased salinity and temperature and accumulation of several potentially toxic substances in receiving waters. All Israeli desalination companies must monitor the coastal area of the Mediterranean around their plants for effects of brine disposal.

Thermal desalination plants are more energy intensive than RO plants, although it’s lower than it used to be with greater efficiencies in technology. And as the Environmental impacts paper notes, depending on the fossil fuel source use, there can also be air pollution issues, specifically with coal.

In Israel, IDE has become a major player in the desalination and water industry. As the Desalination Space and Power paper pointed out IDE:

is owned by the ICL group (50%), controlled by the Ofer brothers, and the Delek group (50%), which is controlled by Isaac Tshuva. The Ofer brothers and Isaac Tsuva are two of the most prominent members of the new capitalist class in Israel. Tshuva is also the main investor in the gas fields recently discovered off Israel’s coast.

Haaretz reported in 2023 that the ICL Group was a serial polluter, topping the Environmental Impact Index, which is published annually by the Environmental Protection Ministry. IDE itself fell foul of a fraud investigation in 2019, which found it produced water with much higher chlorine content, covering up the whole operation, just to save operating costs.

The Ofers are listed as Israel’s richest family, succeeded from the now deceased Ofer brothers, with the empire they built inherited by their children. In 2011, the brothers became embroiled in the Iran scandal, with allegations that the Ofer empire was doing business with Iran, violating US imposed sanctions and resulting in the Ofers being penalised by the US State Department. However rumours surfaced that the Ofers were actually engaged in clandestine operations for Israel. These may have had substance as Meir Dagan, Israel’s recently retired Mossad intelligence agency chief, got fully behind them. As the NYT notes:

The Israeli news media have reveled in exposing links between Ofer-owned companies and former or would-be figures in the Israeli military establishment, and some critics accused the Ofers of trying to create a smokescreen of security ties to legitimize questionable dealings.

Then there was the eulogy from Netanyahu following Sammy Ofers death: “Ofer was a true Zionist.”

Yitzhak Tshuva began his business career as a real estate magnate, but then in 1998 he took control of the Delek Israel Fuel Corporation. The Delek Group played a key role in the discovery of major gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean.

There are two major IDE desalination plants running off coal, with all the associated pollution issues related to coal. But where that coal comes from is just as dark as the fuel itself. As the Canary reported, climate and Palestine solidarity activists gathered outside Glencore’s AGM in Zurich, Switzerland on May 29, 2024 to protest against the company’s complicity with Israel.

Glencore has a long chequered past. As Mongabay notes:

The Switzerland-based miner has a long history of human and environmental rights abuses. In the past decade, it has been entangled in land rights violations, numerous bribery and corruption investigations, court cases, and denunciations by local and international officials, including the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights and the environment.

In particular, its operations in Peru and Columbia has come under scrutiny, with recent reports lambasting the company for its impacts on the local environment and indigenous peoples, who have been affected by mining in the area. European banks are major investors in the company. Despite coal being slated for phasing out due to its higher carbon emissions profile, by being based in Switzerland, Glencore benefits from loopholes that “are not stringent enough to exclude Glencore despite its coal expansion plans.” There has been though some high profile divestments from the company such as the Norwegian Government Pension Fund in 2020.

On 11 June, 2024, Middle east Eye reported on a major break through. An alliance of Palestinian organisations, Colombian trade unionists and indigenous groups has persuaded Colombia's new President Gustavo Petro to halt to the country's coal exports to Israel. Glencore supplies 90% of Colombia’s exports to Israel, with Colombia itself Israel’s primary coal supplier, amounting to 60% of the country’s imports. In may, Petro had severed diplomatic ties with Israel. In the past Israel provided training and equipment in the 1980s to Colombian paramilitaries, responsible for widespread atrocities. Although the embargo won’t have an immediate effect, it will have an impact long term, especially if the groups involved continue to pressure other countries to follow suit with an energy embargo. Ironically South Africa is slated as an alternative supplier of coal to Israel. However once a new government is formed, the coalition intends to put the pressure on to prevent SA dealing with Israel.

A major investor in Israel is the European Investment Bank, which set up a deal worth €900m, in June 2023, with €150 million slated for a seawater desalination facility planned for the Western Galilee to run off renewables. A €500 million credit was issued to Bank Leumi for investing into green projects around the country.

White Phosphorus

Within days of Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, Israel deployed the use of White Phosphorus in Gaza City and on the Lebanon border, as Human Rights Watch reported. WP is an extremely dangerous substance:

White phosphorus ignites when exposed to atmospheric oxygen and continues to burn until it is deprived of oxygen or exhausted. Its chemical reaction can create intense heat (about 815°C/1,500°F), light, and smoke.

Upon contact, white phosphorus can burn people, thermally and chemically, down to the bone as it is highly soluble in fat and therefore in human flesh. White phosphorus fragments can exacerbate wounds even after treatment and can enter the bloodstream and cause multiple organ failure. Already dressed wounds can reignite when dressings are removed and the wounds are re-exposed to oxygen. Even relatively minor burns are often fatal. For survivors, extensive scarring tightens muscle tissue and creates physical disabilities. The trauma of the attack, the painful treatment that follows, and appearance-changing scars lead to psychological harm and social exclusion.

The World Health Organisation provides a detailed account of WP. The use of such weapons are prohibited under Protocol III of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW). It’s not the first time time WP has been used by Israel. It was used previously in 2009. The substance was also used within Lebanon. Both Lebanon and Palestine are signatories to Protocol III, whereas Israel is not.

WP also has a significant environmental impact as detailed in a policy brief from the American University of Beirut, The Socio-environmental Impact of White Phosphorous Ammunition in South Lebanon: Analysis and Risk Mitigation Strategies (2023).

The brief points out that the Protocol is open to interpretation regarding the use of WP as it was originally used by the military to generate dense smoke to camouflage troop movements. Strictly speaking therefore WP isn't technically an incendiary weapon. HRW has been calling for a review of the Protocol. Outlined below is a history of the use of WP in Lebanon.

Environmental damage from WP can be extensive:

Agricultural land is subjected to decreased productivity

Plant dieback

Widespread fire damage

Loss of forest ecosystems and biodiversity

Soil and widespread water contamination of sources exposed

These effects can build up over time as contamination spreads, impacting livelihoods from agriculture and livestock to fishing. According to data:

Between October and November 2023, 462 hectares of forests and agricultural fields have been completely ravaged according to the statements from the ministry of the environment, partially due to WP.

Just like historic Palestine, the Olive industry is important to Lebanon. Attacks have ‘led to the destruction of more than 40.000 ancient olive trees, partially through the use of WP.’ Decontamination can be difficult and extensive as a result of by products produced from WP.

Why the focus on Lebanon? Because it would appear that the use of WP is a precursor to an invasion. This is backed up by a report from Al Jazeera in which an X post from Israel’s Foreign Minister Israel Katz indicated that:

“We are very close to the moment of decision to change the rules against Hezbollah and Lebanon. In an all-out war, Hezbollah will be destroyed and Lebanon will be severely hit.”

The source of WP can be traced to the US, through an Israeli link, namely ICL. A report from Corruption Tracker sheds light into a dark corner. WP is manufactured by the notorious Monsanto Corporation (now Bayer) at St Louis, Missouri. The munitions are made at Pine Bluff Arsenal, Arkansas. The final link in chain is ICL, who provides Monsanto with the phosphates for the manufacture of WP from its chemical manufacturing plant in St. Louis. Codes stamped on the remnants of munitions from Gaza and Lebanon have confirmed the US link.

In the UK, ICL manifests itself as an altruistic company, producing fertiliser to feed the world from its vast ICL Boulby Polyhalite mine located within the North York Moors National Park. It also hosts a dark matter research underground facility, which has attracted significant UK Government funding. ICL has a close relationship with Durham University, which has been a focal point for protests against the University’s ties with entities associated with Israel.

Where do we go from here?

A book published by the Transnational Institute, Dismantling Green Colonialism — Energy and Climate Justice in the Arab Region (2023), covers the wider problem of ‘Eco-Normalisation’. This review from Jacobin outlines the key points. Download the book here.

Right from the word go, Israel has claimed it could make the desert bloom. Apparently that was all that existed before the state was established. That prevailing myth - amongst many - has persisted today, only now, Israel has jumped on the climate crisis bandwagon. The wagon began to roll with the signing of the Abraham Accords with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan in 2020, overseen by the US of course. This has opened up collaboration on various green projects. Jacobin notes:

the Palestinian think tank Al-Shabaka observes that so-called environmentally friendly collaborative projects between Israel and Arab states are a form of eco-normalization. Eco-normalization is the use of “environmentalism” to greenwash and normalize Israeli oppression, and the environmental injustices resulting from it in the Arab region and beyond.

An example of collaboration was the establishment of Project Prosperity at COP27 on Egypt:

According to the terms of the agreement, Jordan will buy two-hundred million cubic meters of water annually from an Israeli water desalination station, which will be established on the Mediterranean coast (Prosperity Blue). The water desalination station will use power produced by a six hundred megawatt (MW) solar photovoltaic plant that will be constructed in Jordan (Prosperity Green) by Masdar, a UAE state-owned renewable energy company.

Israel here is the winner, having previously depleted Jordan’s water accessibility. Its a perfect example of greenwashing to, ‘absolve Israel of its responsibility for the water crisis in Jordan.’ It also serves the neoliberal gospel of commodifying an essential resource. This process is defined as green energy colonialism. Israel will use its technological superiority in this field to further consolidate its settler colonial project in the region. At the end of the day, there is nothing green about Israel. Its entire presence in the region will serve only to destroy the environment, as it destroys everything else. As the conflict in Gaza inexorably approaches a catastrophic end game, Israel will be setting its sights on the vast climate destroying gas fields just off the Gaza coast. That will be the topic of the next article in this series.

Update (20 June, 2024)

Since this article was published, a major new report from Oxfam details the impacts on Gaza’s water and sanitation infrastructure, since October 7. Titled Water War Crimes: How Israel has weaponised water in its military campaign in Gaza, it details how water availability in Gaza has been reduced ‘by 94 per cent to 4.74 litres a day per person – just under a third of the recommended minimum for survival in emergencies and less than a single toilet flush.’ It projects that this could be reduced even further as the conflict continues to a mere 2.48 litres per person per day. The destruction of water and sanitation infrastructure has been widespread and deliberate. As a result, the report concludes:

The impact on public health has been catastrophic, with reported cases of waterborne diseases skyrocketing. Oxfam’s analysis of health data shows that more than a quarter of the population has fallen seriously ill from water and sanitation related diseases, despite these illnesses being preventable with sufficient and safe water and sanitation.